Calydonian boar hunt

The Calydonian boar hunt is one of the great heroic adventures in Greek legend.[2] It occurred in the generation prior to that of the Trojan War, and stands alongside the other great heroic adventure of that generation, the voyage of the Argonauts, which preceded it.[3] The purpose of the hunt was to kill the Calydonian boar (also called the Aetolian boar),[4] which had been sent by Artemis to ravage the region of Calydon in Aetolia, because its king Oeneus had failed to honour her in his rites to the gods. The hunters, led by the hero Meleager, included many of the foremost heroes of Greece. In most accounts it is also concluded that a great heroine, Atalanta, won its hide by first wounding it with an arrow. This outraged many of the men, leading to a tragic dispute.

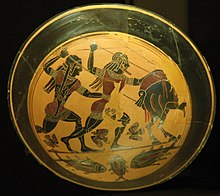

Importance in Greek mythology and art

[edit]

Since the Calydonian boar hunt drew together numerous heroes[5]—among whom were many who were venerated as progenitors of their local ruling houses among tribal groups of Hellenes into Classical times—it offered a natural subject in classical art, for it was redolent with the web of myth that gathered around its protagonists on other occasions, around their half-divine descent and their offspring.[citation needed] Like the quest for the Golden Fleece (Argonautica) or the Trojan War that took place the following generation, the Calydonian boar hunt is one of the nodes in which much Greek myth comes together.[citation needed]

Sources

[edit]Both Homer and Hesiod and their listeners were aware of the details of this myth, but no surviving complete account exists: some papyrus fragments found at Oxyrhynchus are all that survive of Stesichorus' telling;[6] the myth repertory called Bibliotheke ("The Library") contains the gist of the tale, and before that was compiled the Roman poet Ovid told the story in some colorful detail in his Metamorphoses.[7]

Mythology

[edit]The Boar

[edit]

The Calydonian boar is one of several monsters in Greek mythology named for a specific locale. Sent by Artemis to ravage the region of Calydon in Aetolia, it met its end in the Calydonian boar hunt, in which many of the great heroes of the age took part (an exception being Heracles, who vanquished his own Goddess-sent Erymanthian boar separately).

King Oeneus ("wine man")[9] of Calydon, an ancient city of west-central Greece north of the Gulf of Patras, held annual harvest sacrifices to the gods on the sacred hill. One year the king forgot to include Great "Artemis of the golden throne" in his offerings.[10] Insulted, Artemis, the "Lady of the Bow", loosed the biggest, most ferocious wild boar imaginable on the countryside of Calydon.

Ovid describes the boar as follows:[11]

- A dreadful boar.—His burning, bloodshot eyes

- seemed coals of living fire, and his rough neck

- was knotted with stiff muscles, and thick-set

- with bristles like sharp spikes. A seething froth

- dripped on his shoulders, and his tusks

- were like the spoils of Ind [India]. Discordant roars

- reverberated from his hideous jaws;

- and lightning—belched forth from his horrid throat—

- scorched the green fields.

- — Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.284–289 (Brookes More translation)

Ovid goes on to say that the boar rampaged throughout the countryside, destroying vineyards and crops, forcing people to take refuge inside their city walls.[12]

According to Strabo, the boar was said to be the offspring of the Crommyonian Sow vanquished by Theseus.[13]

The Hunt

[edit]Oeneus sent messengers out to look for the best hunters in Greece, offering them the boar's pelt and tusks as a prize.[14]

Among those who responded were some of the Argonauts, Oeneus' own son Meleager, and, remarkably for the hunt's eventual success, one woman—the huntress Atalanta, the "indomitable", who had been suckled by Artemis as a she-bear and raised as a huntress, a proxy for Artemis herself (Kerenyi; Ruck and Staples). Artemis appears to have been divided in her motives, for it was also said that she had sent the young huntress because she knew her presence would be a source of division, and so it was: many of the men, led by Kepheus and Ankaios, refused to hunt alongside a woman. It was the smitten Meleager who convinced them.[15] Nonetheless it was Atalanta who first succeeded in wounding the boar with an arrow, although Meleager finished it off, and offered the prize to Atalanta, who had drawn first blood. But the sons of Thestius, who considered it disgraceful that a woman should get the trophy where men were involved, took the skin from her, saying that it was properly theirs by right of birth, if Meleager chose not to accept it. Outraged by this,[16] Meleager slew the sons of Thestius and again gave the skin to Atalanta (Bibliotheke). Meleager's mother, sister of Meleager's slain uncles, took the fatal brand from the chest where she had kept it (see Meleager) and threw it once more on the fire; as it was consumed, Meleager died on the spot, as the Fates had foretold. Thus Artemis achieved her revenge against King Oeneus.

During the hunt, Peleus accidentally killed his host, Eurytion. In the course of the hunt and its aftermath, many of the hunters turned upon one another, contesting the spoils, and so the Goddess continued to be revenged.[17] According to Homer "the goddess brought to pass much clamour and shouting concerning his head and shaggy hide, between the Curetes and the great-souled Aetolians."[18]

The boar's hide that was preserved in the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea in Laconia was reputedly that of the Calydonian Boar, "rotted by age and by now altogether without bristles" by the time Pausanias saw it in the second century CE.[19] He noted that the tusks had been taken to Rome as booty from the defeated allies of Mark Anthony by Augustus;[20] "one of the tusks of the Calydonian boar has been broken", Pausanias reports, "the remaining one is kept in the gardens of the emperor, in a sanctuary of Dionysus, and is about half a fathom long",[21] The Calydonian boar hunt was the theme of the temple's main pediment.

The Hunters

[edit]According to the Iliad, the heroes who participated in the hunt assembled from all over Greece.[22] Bacchylides has Meleager describe himself and the rest of the hunters as "the best of the Hellenes".[23]

The table lists:[24]

- Those seen by Pausanias on the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea,[25] as well as another hero, Ischepolis, mentioned by Pausanias.[26]

- Those listed by Latin mythographer Hyginus.[27]

- Those noted in Ovid's list from the 8th Book of his Metamorphoses.[28]

- Those listed by the mythographer Apollodorus.[5]

| Hero | Paus. | Hyg. | Ovid | Apd. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acastus | ✓ | Ovid: "swift of dart"[29] | |||

| Admetus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Pheres, from Pherae. | |

| Alcon (son of Hippocoon) | ✓ | One of three sons of Hippocoon from Amyclae, according to Hyginus. | |||

| Alcon (son of Ares) | ✓ | Son of Ares from Thrace. | |||

| Amphiaraus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Oicles, from Argos; "As yet unruined by his wicked wife", i.e. Eriphyle.[30] | |

| Ancaeus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Lycurgus, from Arcadia, killed by the boar. In Ovid's account he wielded a two-headed axe (bipennifer) but he was undone by his boastfulness which gave the boar time enough to charge him: Ancaeus was speared on the boar's tusks at the upper part of the groin and guts burst forth from the gashes it had made.[31] |

| Asclepius | ✓ | Son of Apollo. | |||

| Atalanta | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Daughter of Schoeneus, from Arcadia. |

| Caeneus | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Elatus; Ovid notes that Caeneus was "first a woman then a man".[32] | ||

| Castor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Brother of Polydeuces; the Dioscuri, sons of Zeus and Leda, from Lacedaemon. |

| Cepheus | ✓ | Son of Lycurgus, brother of Ancaeus.[5] | |||

| Cometes | ✓ | Son of Thestius, Meleager's uncle. | |||

| Cteatus | ✓ | One of the two sons of Actor, brother of Eurytus.[33] | |||

| Deucalion | ✓ | Son of Minos. | |||

| Dryas of Calydon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Ares (Hyginus notes him as "son of Iapetus"). | |

| Echion | ✓ | ✓ | One of the Argonauts, son of Hermes) and Antianeira, brother of Erytusson; Ovid says "first to hurl his spear".[34] | ||

| Enaesimus | ✓ | One of three sons of Hippocoon from Amyclae, according to Hyginus. | |||

| Epochus | ✓ | ||||

| Euphemus | ✓ | Son of Poseidon. | |||

| Eurypylus | ✓ | One of the sons of Thestius, according to Apollodorus.[35] | |||

| Eurytion | ✓ | ✓ | King of Phtia, accidentally run through with a javelin by Peleus. | ||

| Eurytus (son of Hermes) | ✓ | ||||

| Eurytus (son of Actor) | ✓ | One of the two sons of Actor, brother of Cteatus.[33] | |||

| Evippus | ✓ | One of the sons of Thestius, according to Apollodorus.[35] | |||

| Hippalmus | ✓ | Along with Pelagon, attacked by the Boar, their bodies taken up by their comrades.[36][37] | |||

| Hippasus | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Eurytus of Oechalia. | ||

| Hippothous | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Kerkyon, son of Agamedes, son of Stymphalos. | |

| Hyleus | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Idas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Aphareus, from Messene; brother of Lynceus. | |

| Iolaus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Iphicles, nephew of Heracles. | |

| Iphicles | ✓ | Amphitryon’s mortal son from Thebes, the twin of Heracles (who took no part).[5] | |||

| Iphiclus | ✓ | One of the sons of Thestius, according to Apollodorus.[35] | |||

| Ischepolis | ✓ | Son of Alcathous (not mentioned by Pausanias as having been seen on the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea).[26] | |||

| Jason | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Aeson’s son, from Iolkos. | |

| Laertes | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Arcesius, Odysseus' father. | ||

| Lelex | ✓ | Of Naryx in Locria. | |||

| Leucippus | ✓ | ✓ | One of three sons of Hippocoon from Amyclae, according to Hyginus. | ||

| Lynceus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Aphareus, from Messene; brother of Idas. | |

| Meleager | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Oeneus. |

| Mopsus | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Ampycus. | ||

| Nestor | ✓ | ||||

| Panopeus | ✓ | ||||

| Pelagon | ✓ | Along with Hippalmus, attacked by the Boar, their bodies taken up by their comrades.[38] | |||

| Peleus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Aiakos, father of Achilles from Phthia. |

| Phoenix | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Amyntor, tutor and companion of Achilles. | ||

| Phyleus | ✓ | From Elis. | |||

| Pirithous | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Ixion, from Larissa, the friend of Theseus. | |

| Plexippus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | One of the sons of Thestius, according to both Ovid and Apollodorus.[35] | |

| Polydeuces | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Prothous | ✓ | ||||

| Telamon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Son of Aeacus. |

| Theseus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Faced another dangerous creature, the dusky wild Crommyonian Sow, on a separate occasion, which according to Strabo,[13] was said to be the mother of the Calydonian boar. |

| Toxeus | ✓ | One of the sons of Thestius, according to Ovid.[35] |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ex-collection the textiles merchant Sir Francis Cook, assembled in Victorian times at Doughty House, in Richmond, south-west London.

- ^ Hard, p. 415, calls it "the greatest adventure in Aetolian legend".

- ^ Hard, p. 416, describes the boar-hunt as being "almost as famous" as the voyage of the Argonauts.

- ^ Rose, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Apollodorus, 1.8.2.

- ^ Strabo, Geography 10.3.6, referring to events of the hunt, does remark "as the poet says".

- ^ Xenophon, Cynegetica x provides some details of boar-hunting in reality; for other classical sources related to boar hunting see Aymard, pp. 297–329.

- ^ The University of Michigan Library, Collection: "Art Images for College Teaching", ID GAS170, title: "Treasury of Sikyon, Delphi: the Calydonian Boar, fragment of a metope".

- ^ Hard, p. 413; Kerényi, p. 115.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 9.533ff.; the poet's concern is with Meleager's role in the battle begun over the boar's carcass, which embroiled Meleager and the Curetes, who were attacking his city of Calydon, rather than with the hunt itself, which he swiftly summarizes in a handful of lines.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.284–289.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.290–299.

- ^ a b Strabo, Geography 8.6.22.

- ^ The pelt remained a trophy at the temple of Tegea, which was enriched with prominent reliefs of the Calydonian boar hunt, in which the Boar took the central place in the composition. The temple, however, was dedicated not to Artemis, but to that other Virgin Goddess, Athena Alea.

- ^ Euripides, fragment 520, noted by Kerényi, p. 119, with note 673.

- ^ According to Diodorus Siculus, 4.34.4, "He had honoured a stranger woman above them and set kinship aside".

- ^ Kerényi, p. 115.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 9.547–549.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.47.2.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.46.1.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.46.5. According to Mayor, pp. 142–143, such a tusk, almost a meter in length, would most likely have been a prehistoric elephant tusk.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 9.543–544.

- ^ Bacchylides, 5.111.

- ^ For alphabetical lists of the hunters given by Pausanias, Hyginus, Ovid, and Apollodorus, see Parada, s.v. CALYDONIAN HUNTERS.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.45.6–7.

- ^ a b Pausanias, 1.42.6.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 173.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.299—317, 360.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.306.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.316–317.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.391—402.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.305.

- ^ a b Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.308, says only that Actor's two sons (Actoridaeque pares) took part in the hunt, without naming them, elsewhere they are Eurytus and Cteatus, see Apollodorus, 2.7.2 with Frazer's note 2.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.345.

- ^ a b c d e According to both Ovid and Apollodorus, the sons of Thestius took part in the hunt, scorned Atalanta, demanded the boar's skin, and were killed by Meleager (Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.432–444; Apollodorus, 1.8.2–3). In Ovid's account of the hunt, the sons were Plexippus and Toxeus; Apollodorus, in his account does, not say who the sons were, but elsewhere (1.7.10) he says the sons were Plixippus, Eurypylus, Evippus, and Iphiclus.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.360–361 (Miller translation revised by Goold); Parada, s.vv. CALYDONIAN HUNTERS, Hippalmus 1.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.360 (Latin ed. Hugo Magnus)

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.360–361 (Miller translation revised by Goold); Parada, s.vv. CALYDONIAN HUNTERS, Pelagon 3.

References

[edit]- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Aymard, J., Essai sur les chasses romaines, Paris 1951.

- Bacchylides, Odes, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1991. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. translated by C. H. Oldfather, twelve volumes, Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae in Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology, Translated, with Introductions by R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma, Hackett Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-821-6.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Kerényi, Karl (1959), The Heroes of the Greeks, Thames and Hudson, London, 1959.

- Mayor, Adrienne, The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times, Princeton University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-691-15013-0.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More, Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses, Volume I: Books 1-8. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library No. 42. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977, first published 1916. ISBN 978-0-674-99046-3. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Parada, Carlos, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, Jonsered, Paul Åströms Förlag, 1993. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Rose, Carol, Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth, W. W. Norton, 2001. ISBN 9780393322118.

- Ruck, Carl A.P., and Danny Staples, 1994. The World of Classical Myth, p. 196

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924). LacusCurtis, Online version at the Perseus Digital Library, Books 6–14.

- Swinburne, Algernon Charles. "Atalanta in Calydon"*