Dorothy Hewett

Dorothy Hewett AM | |

|---|---|

Hewett in 1981 | |

| Born | Dorothy Coade Hewett 21 May 1923 |

| Died | 25 August 2002 (aged 79) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1941–2002 |

| Children | 6 |

Dorothy Coade Hewett AM (21 May 1923 – 25 August 2002) was an Australian playwright, poet and author, and a romantic feminist icon. In writing and in her life, Hewett was an experimenter. As her circumstances and beliefs changed, she progressed through different literary styles: modernism, socialist realism, expressionism and avant garde. She was a member of the Australian Communist Party in the 1950s and 1960s, which informed her work during that period.

In her lifetime she had 22 plays performed, and she published nine collections of poetry, three novels and many other prose works. There have been four anthologies of her poetry. She received many awards and has been frequently included in Australian literature syllabuses at schools and universities. She was regularly interviewed by the media in her later years, and was often embroiled in controversy, even after her death.

Early life and education

[edit]Dorothy Coade Hewett was born on 21 May 1923 in Perth, Western Australia.[1] Until the age of 12, Hewett lived on a sheep and wheat farm, Lambton Downs, in the Western Australian wheat belt.[2] The selection of nearly 2,000 prime acres had been taken by her maternal grandparents in 1912 at Malyalling near Wickepin, and the land was cleared by 15-year-old Albert Facey. It was said of her grandmother Mary Coade that "money stuck to her fingers".[3] Her business acumen made the family wealthy, first in a drapery shop in Perth, then in the wheat belt through farm production, ownership of three local general stores, insider trading in land options along the line of a new railway, and liens on crops and property.[4] Hewett's father survived the Gallipoli campaign and the Western Front in World War I, and he was twice decorated for bravery.[5]

Hewett was educated through correspondence school until age 12. She and her younger sister told each other elaborate stories about the landscape of the farm.[6] She began writing poetry at the age of six, and her parents would wake in the night to write down her poems. Her first poem was published when she was nine years old.[7] On annual trips to Perth, Hewett became entranced with the theatre and the world of Hollywood. Her mother had severe early-onset menopause symptoms and beat the wilful and imaginative young Hewett.[8]

The family moved to Perth in 1935 where they opened the Regal Theatre in Subiaco. Hewett attended Perth College, where she had to wear shoes, hat and gloves for the first time, a shock after her ragamuffin life on the farm.[9] As a painfully shy country girl, she was known as "Hermit Hewett".[10] She excelled at English and received the State Exhibition award in English in 1941. To assist his talented daughter, her father took her to a meeting of the Fellowship of Australian Writers.[11]

Hewett enrolled at the University of Western Australia (UWA) in 1942, where she participated eagerly in university life. She won the national Meanjin poetry award that year, aged 17.[12] With several friends she founded the University Drama Society and acted in a number of Repertory plays, including a melodrama that she wrote herself.[13] She received high distinctions in English, but failed French for several years and did not graduate.[10]

Realist writer period and the Communist Party

[edit]After leaving UWA, Hewett worked in a bookshop and as a cadet journalist with the Perth Daily News, but lost both these jobs. She rejected the lifestyle and aspirations of her wealthy parents and eventually joined the Communist Party of Australia (CPA). She briefly edited the Communist Party newspaper The Workers' Star.[14] Dozens of articles authored by Dorothy Hewett appear in the Worker's Star from 1945 to 1947.[15] Recuperating after an attempted suicide[a] following a failed wartime relationship, she wrote the poem Testament, her first mature work, which won the prestigious ABC Poetry Prize in 1945.[17] On the rebound, she married the Party lawyer Lloyd Davies that year and their child Clancy was born in 1947.[18]

After World War II she briefly re-enrolled at UWA and became editor of the university journal, Black Swan, soon nicknamed "Red" Swan.[19] Her enthusiasm was such that she kept the journal 'politically pure' by writing most of the contents herself under various noms de plume.[20] The authorities banned it from distribution in any other Australian university.

Hewett covered the 1946 Pilbara Strike for the Worker's Star,[21] and wrote the epic ballad, Clancy and Dooley and Don McLeod,[22] which cemented her position as a radical author and a supporter of Indigenous rights. However, she then virtually discontinued writing for a life of activism and child-rearing.[1]

In 1949, she fell in love with the boilermaker Les Flood, and eloped with him to Sydney, to live in the inner-city suburb of Redfern. The CPA strongly disapproved of what they called immoral behaviour and she had to restart at the bottom, selling the Communist weekly paper Tribune on the street, and leafleting. The time she spent living in poverty in Kings Cross and Redfern and volunteering for the CPA informed some of her later works.[23] In the period of McCarthyism their house was a regular meeting place for the CPA, devoted to printing and distributing material opposing the Communist Party Dissolution referendum and later the Petrov Commission. During this period, Hewett wrote mostly journalism, under pseudonyms, for the Tribune.[24]

The following year her first child, Clancy, died of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Melbourne, an event which was to have a profound effect on the rest of her life.[25][b]

In 1952, Hewett and Flood joined a trade union delegation to Russia, and they were among the first Westerners to visit the new People's Republic of China.[3]

Hewett worked for a year as a mill hand in a cotton spinning mill, which gave her the material for her first novel, Bobbin Up. The climatic moment is a strike by the women workers against poor working conditions and unfair dismissals. The style and content are firmly rooted in socialist realism.[26] Bobbin Up was translated into five languages.[27]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Hewett engaged in debates about literature and social change from a committed Marxist perspective.[28] She was one of the founders of the left-wing organisation the Union of Australian Women,[29] editing the first edition of their journal,[30] and she participated enthusiastically in Realist Writers groups in Sydney and Perth.[31]

Flood had recurring paranoid schizophrenia, untreatable at the time, and was unable to work. Hewett took a job as a copywriter on the catalogue of Walton Sears Department Store to support the family, and then with Leyden Publishing. In 1958, as Flood became increasingly violent and dangerous, she fled back to her parents in Western Australia (WA) with their three small boys Joe, Michael and Tom Flood.[3]

In South Perth her parents built a house for her on the old tennis court at the back of their property. Rebuilding her life, Hewett trained at the Graylands Teachers' College but was removed when they found she had been not only married but divorced.[10]

In 1960, she married the poet, cane cutter and seaman, Merv Lilley. Lilley had been a foundation member of the Bush Music Club,[32] and he introduced the family to folk music, which was beginning its revival.[33] In late 1961, the family, which now included one-year-old Kate Lilley, travelled to Queensland with a caravan to visit Lilley's family. Before leaving WA, Hewett and Lilley roneoed a joint volume of their poetry What About the People![34] In the next few years a number of these poems were put to music by aspiring folk singers. Weevils in the Flour, a song about the Depression childhood of her friend Vera Deacon,[35] has been a favourite with union choirs and folk singers, with a folklore all of its own.[36] Another song, Sailor Home From the Sea, has been recorded under four different tunes.[37]

Les Flood had been sighted in WA, and to avoid him, the family remained in Queensland for a year and bought an old house in Wynnum, Brisbane. The house had no water or sewerage and Hewett caught an intestinal bug. Afterwards she had ongoing health problems that often confined her to bed.[3]

During 1962, the family participated in the radical salon society along the Brisbane foreshore, led by John Manifold the folklorist and poet.[38] With Nancy Wills, Hewett wrote a short political musical play Ballad of Women, which contains many of the Brechtian elements and figures of her later musicals.[39] She began to publish new poems in Tribune, mostly paeans to socialism.[40] As they made the long return journey to Perth on the Trans Australian Railway at the end of the year, Hewett went into labour with her sixth child and the baby Rozanna was delivered in Kalgoorlie.[3]

In Perth, Hewett completed her Arts degree and obtained a position as a university tutor in English at the UWA,which she held until 1973. She financially supported her family with some help from Lilley and her parents.[3]

Hewett made a trip to a Weimar Writer's Conference in 1965,[41] and was treated for thrombosis in the Soviet Union. Here she became aware of the plight of dissident writers under the heavy censorship regime of the Soviet bloc. Hewett arranged protests on behalf of the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial in 1965,[42][c] after which she became increasingly disillusioned with Communism. In 1967, she wrote her first full-scale play This Old Man Comes Rolling Home,[43] which remains popular today.[44] This would be her last work of socialist realism.

During the Prague Spring in 1968 she was a strong supporter of the moderate Czech regime. She and Lilley organised a protest march in Perth with students and the CPA.[45] Although the CPA distanced itself from the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hewett subsequently left the Party along with many others. She was attacked by former friends who remained Stalinist hardliners.[46]

Mature work

[edit]In 1968 her first volume of verse Windmill Country[47] was published, including all her best poems up to that time.

Concerned about critical comments that her first play was dated, she wrote an overtly outré play, the "savage but hilarious attack on academic suburbia" Mrs Porter and the Angel. It caricatured members of the UWA English department, so the play was unable to be staged in Perth for fear of defamation proceedings,[48] and it was first performed at the PACT Theatre in Sydney in May 1969.

She continued with a series of expressionist plays. At the end of 1970, her tour-de-force play The Chapel Perilous was staged in Perth. The self-parodying hero, Sally Banner, resonated with the emerging feminist movement and ensured Hewett's lasting fame. She followed it in 1972 with Bonbons and Roses for Dolly, a musical play about failed dreams set in an idealised Regal Theatre.[49]

In 1973, Hewett received the first of eight grants[50] from the new Literature Board of the Australia Council. She was over 50 years old when she was at last enabled to become a full-time professional writer.[19]

She returned in late 1973 to her "city of marvellous experience" Sydney,[19] where she bought a rambling terrace in Woollahra with her share of her recently deceased mother's estate. Here she enjoyed her most productive years, creating in quick succession: The Tatty Hollow Story (a woman who cannot be defined by her former lovers); The Golden Oldies (for two actors and two dummies); the opera extravaganza Joan (her only work set outside of Australia, with 75 actors and 40 musicians); the show musical Pandora's Cross; the rock opera Catspaw; The Fields of Heaven for the Festival of Perth; and two books of poetry Rapunzel in Suburbia and Greenhouse. In 1977 she wrote her most popular play The Man from Mukinupin.[51]

In collaboration with poets associated with the "Generation of '68"[52] and New Poetry magazine,[53] particularly Robert Adamson (with whom she maintained a close lifetime friendship), her work became more sparse and directed and the romantic element more controlled.[19]

In 1981, after her children had left home, she moved to another large, semi-ruined terrace in the centre of Darlinghurst. In the 1980s, she published the poetry collections Alice in Wormland and Peninsula. The latter was written in Portsea, Melbourne, in a cottage "Imara" made available to writers by Neilma Gantner.[54] A number of less-successful plays were trialled, sometimes in playhouses in country towns. Towards the end of her time in Darlinghurst, she wrote the first volume of her autobiography Wild Card, which covers the years 1923 to 1958.[6] She completed the book during a trip to Oxford, England.[55] Encouraged by its success, she continued with further works.

Later years

[edit]

Hewett moved at the end of 1991 to an old coach house at Faulconbridge in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. She wrote two moderately successful novels, and a poetry collection Halfway Up the Mountain, but struggled to get new theatre work onto the stage[51] until she wrote the successful play Nowhere, which was staged in 2001. She was disabled by osteoarthritis and was progressively reliant on a wheelchair and then bedridden. Her husband Lilley cared for her into his eighties. She died from recurring breast cancer on 25 August 2002.[56] At the time of her death she was working on the second volume of her autobiography.[57]

Literary style and contribution

[edit]Virtually all encyclopaedias of, and companions to, post-war writing in English[d] and women writers[58] include Hewett as a playwright and poet. According to The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature, Hewett used "poetry, music and symbol to portray life's paradoxes and her characters' mingling of perception and delusion" while adding "her verse is confessional and romantic in theme, wryly humorous, frankly bawdy, varied in tone and rich in imagery".[59]

D'Aeth finds a "dizzying amplitude of styles in her work, beginning with modernism in her early poems through socialist realism to expressionist musical farce, followed by a late response to American poetic experimentation in the 1950s and 1960s", citing her trademark "vivid phantasmagoria and baroque larrikin humour". Even a single play like The Chapel Perilous employs tragedy, farce, naturalism, Brechtian expressionism and musical comedy in quick succession.[4] In fact, Hewett paid scant attention to convention or literary fashion, following her own muse on topics she believed were important. Even during her Realist Writer period, her works were much more passionate and dramatic than was normal for the socialist realism genre.[60]

She and Alma De Groen were almost the only female playwrights during the Australian drama renaissance of the 1970s.[61] When most plays of the time were naturalistic along the style of TV dramas, Hewett's plays incorporated allusion, mystery, landscape, poetry, songs and music, with lashings of ironic humour that saved her characters from excessive posturing. Much of her work was autobiographical and intensely personal, and several works were set in her childhood dreamscape of wheatbelt Western Australia.[4]

Hewett worked directly with most of the major directors and actors of the time, and was her own dramaturg during first-time performances. Female actors particularly appreciated the strong roles they were given in Hewett's plays.[62][63]

Various musicians have set Hewett's words to music. Weevils in the Flour has been recorded six times, most notably by Declan Affley and The Bushwackers. Robyn Archer recorded a rock version of Hewett's poem In Moncur Street.[64][65] A number of composers worked with Hewett on music for her plays, notably Jim Cotter and Patrick Flynn. While the lyrics in the plays were published with the text, unfortunately the music was never published or recorded, so it usually had to be re-composed for any subsequent staging.[e]

She was appointed as Writer in Residence in eight Australian universities and one in the USA between 1975 and 1990,[50] where she participated fully in university life, giving encouragement to younger writers.[66]

Her very late emergence as a major figure prevented her travelling abroad to publicise her work to any extent. Bobbin Up was published throughout Europe and therefore is well known internationally. However, with the exception of The Man from Mukinupin, which was staged in London,[67] her plays never found their way outside Australia.

Personal life

[edit]For much of her life after 1960, Hewett struggled with ill-health, apart from a very active period in the 1970s. She had thrombosis from 1965. Her ongoing gastric trouble and a slipped retina were corrected by surgery in 1971–2. Progressive osteoarthritis restricted her mobility from the late 1970s, and many of her later works were written in bed, where she also received visitors.[3]

The necessity to support a large family was also a major limitation on her activity. She only became a full-time writer from the age of 51, with the aid of Literature Board grants, intermittent earnings from writing and from university fellowships, and an ongoing bequest from her father's estate.[68]

In public, Hewett was a great entertainer and a charismatic personality who was always surrounded by a circle of admirers and friends. In private she was rather shy but also immensely entertaining. Due to a series of illnesses she spent a good deal of time after 1961 in her bed, apart from a very active period in the 1970s. She would move from near-inertness to creative bursts of highly directed writing activity. She wrote her first novel in eight weeks and re-wrote many of her plays in the theatre on-the-fly, in collaboration with the director and the actors. The first draft of her final play Nowhere she wrote in only three days at the age of 78.[69]

Despite her enduring shyness, Hewett loved being part of a community, whether it was the people in the rural towns of her youth in the 1930s, the Redfern slum dwellers in the early 1950s, the CPA involvement of 1945–1967, the university communities of the late 1960s, or the Bohemian city cliques of the 1970s. She was resolute in pursuit of her ideals, marginalising at various times partners, financial security and even her children to writing, socialism or her search for romantic passion. However, all five of her adult children were successful in their chosen fields.[3]

Hewett encouraged and constructively criticised the work of young poets and her house became a meeting-place for struggling writers. In Perth, weekly meetings were held where poets read their work, and lively social events were attended by writers, students, actors and intellectuals. She had many friends of different political persuasions.[3] At Woollahra, even more than in South Perth, the open house was almost a nightly event. Crowds of young writers, musicians and artists gathered, and well known figures from the literary, arts and political scene were often present.[70] She continued to be visited in her later residences by interviewers, arts figures and fans of her work.[3]

Controversies

[edit]Throughout her life, Hewett was no stranger to controversy and sometimes revelled in it.

Her early romantic involvements, her attempted suicide and her membership of the CPA greatly distressed her parents and grandparents. On the other hand, when she left the CPA she was strongly attacked by hard-line Communist colleagues, though the Party always claimed her as their own. Padraic McGuiness attacked her as a former Communist immediately after her death.[71]

The subject matter and language of her plays could be shocking to members of her audience. The publisher sent warnings to school librarians to return Chapel Perilous if necessary, and most of them did.[61] Women rushed out of a performance of Bonbons and Roses in tears when menstruation took place on stage, and flowers were placed in the theatre toilets in protest. Mixed reviews and modest box office takings caused the hyped musical Pandora's Cross to shoulder part of the blame for the failure of the new Paris Theatre company in 1978.[72]

Hewett's characters and locations often derived from real life but could sometimes be too thinly disguised. In 1977, her first husband Lloyd Davies sued her for libel for a poem "The Uninvited Guest"[73] – possibly the first time someone has been sued for a poem. The action was protested across the nation, with the South Australian Parliament choosing to read the poem into its records.[51] Several fundraising events[74] opposing censorship were held to help defray the legal defence costs,[75] and Bob Hudson recorded a satirical song "Libel" to assist.[76] The matter was settled out-of-court, the book was recalled and the offending poem was removed. The plays The Chapel Perilous and The Tatty Hollow Story, which contained unflattering depictions of a Davies-like character, could not be shown in Perth. Davies subsequently wrote a rambling defence of his lawsuit and conducted a lecture tour in support.[77]

Hewett was outspoken in defence of Australian literature, especially in her later years. In 2000 Hewett launched a broadside at lack of support for writers by publishing houses and governments, saying independent publishing houses were being taken over by big overseas companies, that the price of books was rising, and only generous public funding would enable experimental writing and young, unknown writers to find a place.[78]

In 2018, fifteen years after her death, Hewett's two daughters appeared on the front page of The Australian,[79] and in other media interviews. The women stated that they had been very sexually active as teenagers in the 1970s, with their parents' knowledge and tacit approval.[80] Some of their sexual activity had been conducted with adult visitors to Woollahra, specifically naming the political writer Bob Ellis, Martin Sharp and other deceased celebrities. Kate Lilley asserted that on several occasions, sex with unnamed men had not been consensual. The two women believed their mother had not ensured their safety.[25] The accusations were not confirmed and no charges were laid.

A media frenzy ensued, in which the tabloid press attacked "paedophile rings", the libertarian 1970s, Hewett's lapsed Communism, and Ellis in particular, who was detested by conservatives. The Australian Senate passed a motion raised by Senator Cory Bernardi, calling for renaming of the Dorothy Hewett Award at the University of Western Australia. The university did not comply.[81]

Recognition, awards, legacy

[edit]

Hewett has been called "one of Australia's best-loved and most respected writers".[56]

She is regarded as one of the success stories of the Australia Council programme of government grants to writers. She was awarded eight grants including a lifetime Emeritus Grant from the Literature Fund of the Australia Council. She was awarded a D.Litt. from the University of Western Australia in 1996.[50]

Her literary awards include:[82]

- 1940: Meanjin poetry prize

- 1945 and 1965: ABC National Poetry Prize

- 1957: Mary Gilmore Award, for the short story "Joey" (published 1961)[1]

- 1974 and 1982: Australian Writers' Guild Award

- 1976: International Women's Year Grant

- 1986: The Australian Poetry Prize

- 1989: Grace Leven Prize for Poetry

- 1991: Mattara Poetry Prize

- 1991: Victorian Premier's Prize for Nonfiction

- 1993: Australian Artists Creative Fellowship

- 1994: Turnbull Fox Phillips Banjo Award.

- 1994, 1996, 2001: Western Australian Premier's Book Awards, for Poetry

- 1996: Christopher Brennan Award

Other recognition includes:

- 1986: Hewett was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in the 1986 Australia Day Honours for service to literature[83]

- 1990: A painting of Hewett by artist Geoffrey Proud won the Archibald Prize[84]

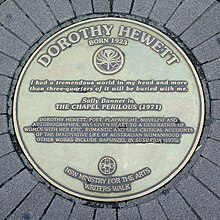

- 1991: Writers Walk plaque at Circular Quay laid[85][86]

- 2000: Western Australian Writers Hall of Fame[1]

- 2000: New South Wales Premier's Literary Awards, Special Award[1]

- 2007: Hewett Crescent, in Franklin a suburb of Canberra, is named for her[87]

- 2015: Dorothy Hewett Award for an unpublished manuscript established by UWA Publishing in honour of Hewett, "as an outstanding writer who was born in this place and spent decades here as a writer, a university teacher, and a mentor to many"[88]

Works

[edit]In her lifetime Hewett had 22 plays performed, and she published nine collections of poetry, three novels and many other prose works.[f] There have been four anthologies of her poetry.

Plays and music theatre

[edit]- Ballad of Women (with Nance Macmillan) (1961)[89]

- This Old Man Comes Rolling Home (Sydney: Currency Press, 1967)[90]

- Mrs Porter and the Angel (1969)[91][48]

- The Chapel Perilous (Sydney: Currency Press, 1972)[92] (first performed in January 1971)

- Bon-Bons and Roses For Dolly (Sydney: Currency Press, 1972)[49]

- Catspaw (1974)[93]

- The Knight of the Long Knives (1975)[94]

- Miss Hewett's Shenanigans (1975)[74]

- The Beautiful Miss Portland (1976)

- The Tatty Hollow Story (Sydney: Currency Press; London, Eyre Methuen, 1976)[95] (written in 1974)

- The Golden Oldies (Sydney: Currency Press, 1977)

- Pandora's Cross (Budapest: Centre hongrois de l'I.I.T., 1978)[96]

- The Man From Mukinupin (Fremantle Arts Centre Press; Sydney: Currency Press, 1980)[97]

- Susannah's Dreaming (1980)[98]

- The Fields of Heaven (1982)

- Christina's World (1983) (Operetta)[99]

- Joan (Montmorency, Victoria: Yackandandah Playscripts, 1984)[100] (performed in 1975)

- Golden Valley (Paddington, N.S.W.: Currency Press, 1985)[101] (performed in 1981)

- Song of the Seals (Sydney: Currency Press, 1985)[101]

- Me and the Man in the Moon (1987)

- The Rising of Pete Marsh (1988)

- Zoo (1991) (with Robert Adamson)

- Zimmer: A Mock Opera in Two Acts (1993) (with Robert Adamson)[102]

- Jarrabin trilogy (1996)[103]

- Nowhere (Strawberry Hills, N.S.W.: Currency Press, 2001)[104]

Poetry

[edit]- What About the People! ([Sydney]: National Council of the Realist Writer Groups, 1962)[105] (with Merv Lilley)

- The Hidden Journey (Newnham: Wattle Grove Press, 1967)[106]

- Windmill Country (Melbourne: Peter Leyden Publishing House, 1968)[107]

- Rapunzel in Suburbia (Sydney: Prism Books, 1975)[108]

- Greenhouse (1979)

- Journeys (1982) (with Rosemary Dobson, Gwen Harwood & Judith Wright)

- Alice in Wormland (Newcastle Upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1990)[109]

- Peninsula (South Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1994)[110]

- Wheatlands (South Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2000) (with John Kinsella)[111]

- Halfway Up the Mountain (Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 2001)[112]

- The Gypsy Dancer and Early Poems (Sydney: Juvenilia Press, 2009)[113]

Poetry anthologies

[edit]- A Tremendous World in Her Head: Selected Poems (Sydney: Dangaroo Press, 1989)[114]

- Selected Poems, edited by Edna Longley (South Fremantle, W.A.: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1991)[115]

- Collected Poems 1940–1995, edited by William Gronow (South Fremantle, W.A.: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1996)[116]

- Selected Poems, edited by Kate Lilley (Crawley, W.A.: UWA Publishing, 2010)[117]

Prose

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Bobbin Up (Melbourne, Victoria: Australasian Book Society, 1959)[118]

- The Toucher (Ringwood, Victoria: McPhee Gribble, 1994)[119]

- Neap Tide (Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books, 1999)[120]

Other

[edit]- Wild Card: An Autobiography, 1923–1958 (London: Virago Press, 1990)[121]

- A Baker's Dozen (Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia, 2001)[122]

- Selected Prose of Dorothy Hewett, edited by Fiona Morrison (Crawley, Western Australia: UWA Publishing, 2011)[123]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Daily News 6 June 1945, preserving propriety, stated Dorothy was suffering from mumps and poisoned herself by accident.[16]

- ^ Hewett's grandson Nathaniel Cervas Flood also died of ALL in 2010, aged 7.

- ^ Her 1967 poem 'The Hidden Journey' Overland 36, one of her best, describes her reservations lyrically and pointedly.

- ^ See The Continuum Companion to Twentieth Century Theatre, The Companion to Theatre and Performance, The Oxford Companion to Modern Poetry, The Companion to Theatre and Performance, and The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English.

- ^ For example, The Man from Mukinupin, which has 21 songs, had original music by Jim Cotter in its 1979 Perth staging, and music by Elizabeth Riddle in its 1981 Sydney staging. Because there was a recording, later productions used Cotter's music.

- ^ Austlit finds 745 works by Hewett, 415 works about the author, and 27 awards.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Dorothy Hewett". AustLit. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Novakovic, Jasna (2010). "Dorothy Hewett's sacred place" (PDF). Australasian Drama Studies. 56: 203–217.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Flood, Joe (2013). "Dorothy Hewett and her forbears". Unravelling the Code: The Coads and Coodes of Cornwall and Devon. Melbourne: Deluge. pp. 362–369, 668–671. ISBN 9780992328108. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Tony Hughes-d'Aeth. (2017). 'Dorothy Hewett', Chapter 6 in Like Nothing on this Earth: A Literary History of the Wheatbelt. UWA Publishing.

- ^ Hewett, Arthur Thomas. "The AIF Project". www.aif.adfa.edu.au.

- ^ a b Hewett, Dorothy (2012). Wild Card: An Autobiography 1923-1958. UWA Publishing. ISBN 978-1-74258-395-2.

- ^ Dorothy Hewett (1933). "Dreaming", Our Rural Magazine.

- ^ Wild Card, pp. 25, 31, 50.

- ^ Wild Card, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Lynne. Hunt, L. & Trotman, J. (2002) Claremont Cameos. Edith Cowan University: Perth – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Wild Card, p. 63.

- ^ "Play evening: function at the university". The West Australian. 11 September 1941. p. 7.

- ^ The West Australian 22 August 1941, 5 September 1941, 4 July 1942, 16 November 1945.

- ^ Williams, Justina (1993). Anger and love. Arts Centre Press. ISBN 9781863680417.

- ^ "Search". Trove.

- ^ "Takes Poison by Mistake - the Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1955) - 6 Jun 1945". Trove. 6 June 1945.

- ^ "Writes prize poem after breakdown". Daily News. 31 May 1945. p. 11. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Wild Card, p.133.

- ^ a b c d Hewett, Dorothy (December 1982). "The garden and the city". Westerly. Vol. 27. pp. 99–104.

- ^ 'Black Swan'. The West Australian 26 July 1946, 22 Oct 1947.

- ^ "W A writer on native struggle". The Workers Star. p. 6. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Clancy and Dooley and Don McLeod". unionsong.com.

- ^ "Trove". trove.nla.gov.au.

- ^ "Dorothy Hewett, interviewed by Terry Lane in 1978". AustLit.

- ^ a b Lilley, Rozanna (2018). Do Oysters get Bored. Perth: UWA Press. ISBN 9781742589633.

- ^ Susan McKernan (1989). A Question of Commitment: Australian Literature in the Twenty Years after the War. Allen and Unwin.

- ^ Knight, Stephen (1995). "Bobbin Up and the working class novel". In Bennett, Bruce (ed.). Dorothy Hewett: Selected Critical Essays. Fremantle Arts Centre. ISBN 1863681132.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy. "Dorothy Hewett: two early essays 'Eat Bread and Salt and Speak the Truth', and 'The Times They are a'Changin'". Hecate. 21 (2): 129–136 – via search.informit.org (Atypon).

- ^ "1950's 1960's - A History of International Women's Day". www.isis.aust.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Zora Simic". www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au.

- ^ "John McLaren. A failed vision: Realist Writers' Groups in Australia 1945-65: the case of Overland" (PDF). vuir.vu.edu.au.

- ^ "Bush Music Club Inc. - Australian folk music and dance". www.bushmusic.org.au.

- ^ Fahey, Warren (17 September 2014). "Australian Folk Revival". Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Kevans, Denis (4 December 1963). "These poems are big as life…'". Tribune. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (30 November 1960). "Where I grew to be a man". Tribune. p. 7. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Gregory, Mark (2009). "Industrial song and folksong" (PDF). Australian Folklore. 24: 91–96.

- ^ "Sailor Home from the Sea (Cock of the North)". Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "John Manifold | Mapping Brisbane History". mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au.

- ^ "The ballad of women / [Nance Macmillan and Dorothy Hewett] - Fryer Library Manuscripts". University of Queensland Library.

- ^ Poems in Tribune "To the Communists", 19 September 1962 and 'Three men' 9 January 1963. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article236853283

- ^ Moore, Nicole; Spittel, Christina (2018). "Bobbin Up in the Leseland". In Kirkpatrick&Dixon (ed.). Republics of Letters: Literary Communities in Australia. Sydney University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781783085248.

- ^ Milliss, Roger (25 September 1968). "'Review, Windmill Country. The odyssey of Dorothy Hewett". Tribune. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Rounding out a slice of life". Tribune. 25 January 1967. p. 6. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "This Old Man Comes Rolling Home". UNSW Theatrical Society.

- ^ "Protest cables from Perth". Tribune. 11 September 1968.

- ^ Williams, Victor (27 September 1967). "Anti-soviet propaganda". Tribune.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1968). Windmill Country. Overland in conjunction with Peter Leyden Publishing House.

- ^ a b Hewett, Dorothy (1900), Mrs. Porter and the angel : a modern fairytale in two acts, retrieved 20 August 2016

- ^ a b Hewett, Dorothy (1976), Bon-bons and roses for Dolly ; The Tatty Hollow story : two plays, Currency Press, ISBN 978-0-86937-047-6

- ^ a b c "Hewett, Dorothy (Coade)". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Moore, Nicole (1 August 2018). "Dorothy Hewett: 1923 – 2002". Search Foundation. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Shapcott, Tom (1996). "Generation of '68". The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-century Poetry in English. Oxford.

- ^ "National Library of Australia New Poetry collection". Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Peninsula: author Dorothy Hewett". Austlit. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (2015). "The empty room". Westerly. 60 (1): 10–13.

- ^ a b Birns, Nicholas; McNeer, Rebecca (2007). A Companion to Australian Literature Since 1900. Camden House companion volumes. Camden House. pp. 321–. ISBN 978-1-57113-349-6. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Hewett, Dorothy (1923-2002)". The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Buck, Claire (1994). "Hewett, Dorothy". Women's Literature A-Z. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747519539.

- ^ Wilde, William H.; Hooton, Joy; Andrews, Barry (1994), "Hewett Dorothy", The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195533811.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-553381-1, retrieved 2 August 2022

- ^ Morrison, Fiona (2012). "Leaving the party: Dorothy Hewett, literary politics and the long 1960s". Southerly. 72.

- ^ a b Meyrick, Julian (2018). Australian Theatre After the New Wave. Boston: Brill. pp. 52–3. ISBN 9789004339880.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Peter (1979). "Dorothy Hewett". After 'The Doll': Australian Drama since 1955. Melbourne: Edwin Arnold. pp. 145–156. ISBN 0-7267-2040-2.

- ^ Schafer, Elizabeth (1994). "Golden girls and bad girls: the plays of Dorothy Hewett". Australian Writing Today. 6 (1): 140–145. JSTOR 41556571 – via jstor.

- ^ Robyn Archer (1978). Wild Girl in the Heart. Larrikin. http://www.45worlds.com/vinyl/album/lrf027

- ^ Archer, Robyn (19 August 2021). "In Moncur Street". Youtube.

- ^ Hughes, Tash (2003). "Rapunzel in Suburbia: a portrait of Dorothy Hewett". Writer Tash Hughes.

- ^ "The Man from Mukinupin : A Musical Play in Two Acts | AustLit: Discover Australian Stories". www.austlit.edu.au.

- ^ "Dorothy Hewett (1923-2002)". Doollee.com: The Playwrights Database. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (2001). "Introduction from the author". Nowhere. Sydney: Currency Press. ISBN 0868196479.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1983). "The Darkling Sisters". A Baker's Dozen. Penguin Books. pp. 204–226. ISBN 9780141001326.

- ^ Flood, Joe (29 November 2002). "Poet fought tyranny: letter to the editor". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "The constructive critic". Australian Financial Review. 3 December 2004. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Tozer, Kate; Colvin, Mark (26 August 2002). "PM - 26/08/2002: Dorothy Hewett passes away". ABC Radio National. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b Hewett, Dorothy (1975). "Miss Hewett's Shenanigans". Austlit. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, David (16 September 1976). "Poet's fight starts libel reform bid". The Australian. p. 1. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Bob Hudson (1980). 'Libel' on Party Pieces. Larrikin.[1] 29:15

- ^ Davies, Lester Lloyd (1987). In defence of my family. Perth: Peppy Gully Press. ISBN 0958864608.

- ^ Brice, Chris (6 March 2000). "Author's strong words on a day of high note". The Adelaide Advertiser. p. 11.

- ^ Neill, Rosemary (9 June 2018). "Mum's men used us for under-age sex". The Australian. p. 1.

- ^ Nichols, Claire (21 June 2018). "Dorothy Hewett's daughters Rozanna and Kate Lilley talk about re-casting their mum's image in the age of #MeToo". ABC News. Radio National: The Hub on Books. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Books+Publishing. "Dorothy Hewett Award to retain name". Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Dorothy Hewett | Awards". Austlit. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Dorothy Coade Hewett". honours.pmc.gov.au. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ "Archibald Prize Archibald 1990 work: Dorothy Hewett by Geoffrey Proud". Art Gallery of NSW. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "The Chapel Perilous - A Reading Australia Information Trail". AustLit. 23 June 1927. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Gorman, James (16 April 2014). "Circular Quay's Writers Walk plaques out of date for deceased Australian authors". The Daily Telegraph (Sydney). Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Public Place Names (Franklin) Determination 2007 (No 1)" (PDF). ACT Government. 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Dorothy Hewett and the Dorothy Hewett Award". UWA Publishing. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "The ballad of women / [Nance Macmillan and Dorothy Hewett] - Fryer Library Manuscripts". manuscripts.library.uq.edu.au.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1976), This old man comes rolling home, Currency Press, ISBN 978-0-86937-049-0

- ^ Mrs Porter and the Angel (18 May 1969 - 1 June 1969) [Event description], 1969, retrieved 20 August 2016

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1972), The chapel perilous : (or, The perilous adventures of Sally Banner), Currency Press, ISBN 978-0-85893-008-7

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1900), Catspaw : a musical in two acts, retrieved 20 August 2016

- ^ Novakovic, Jasna (2008). "The Knight of the Long Knives". Southerly. 68: 139–149.

- ^ The Tatty Hollow Story by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Pandora's Cross by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ The man from Mukinupin by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1980). The Golden Oldies/ Susannah's Dreaming. Paddington, New South Wales: Currency Press. ISBN 9780868190310.

- ^ Edwards, Ross (1983). "Christina's World (1983)". RossEdwards. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy; Flynn, Patrick, 1936-2008 (1984), Joan, Yackandandah Playscripts, ISBN 978-0-86805-009-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hewett, Dorothy (1985). The Golden Valley/ Song of the Seals. Currency Press. ISBN 978-0868191065.

- ^ "Zimmer: A Mock Opera in Two Acts. Yackandandah Playscripts". Worldcat. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "Talk of the town plucked from the too-hard basket". Sydney Morning Herald. 16 October 2001.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (2001). Nowhere. Strawberry Hills NSW: Currency Press. ISBN 0868196479.

- ^ What About the People! by Dorothy Hewett and Merv Lilley, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Hidden Journey by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Windmill Country by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Rapunzel in Suburbia by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Alice in Wormland by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Peninsula by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Wheatlands by Dorothy Hewett and John Kinsella, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Halfway Up the Mountain by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ The Gypsy Dancer & Early Poems by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ A Tremendous World in Her Head: Selected Poems by Dorothy Hewett, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy; Longley, Edna (1991). Selected poems. South Fremantle, W.A: Fremantle Arts Centre Press. ISBN 978-1-86368-004-2.

- ^ Collected Poems 1940–1995, by Dorothy Hewett, edited by William Grono, worldcat.org. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Selected poems of Dorothy Hewett | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1959). Bobbin up. Melbourne: Australasian Book Society.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1994). The toucher. Ringwood, Vic: McPhee Gribble. ISBN 978-0-86914-330-8.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1999). Neap tide. Ringwood, Vic: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-028843-8.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (1990). Wild card: an autobiography, 1923-1958. London: Virago. ISBN 978-1-85381-143-2.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy (2001). A baker's dozen. Ringwood, Vic: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-100132-6.

- ^ Hewett, Dorothy; Morrison, Fiona (2011). Selected prose of Dorothy Hewett. Crawley, W.A: UWA Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921401-62-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Adelaide, Debra. Australian Women Writers: A Bibliographic Guide . London. Pandora. ISBN 0-86358-149-8

- Guide to the Papers of Dorothy Hewett at National Library of Australia, September 2007

- Lilley, Kate. "In the Hewett Archive". JASAL Special Issue: Archive Madness: 1–14.

- Morrison, Fiona. "The Quality of Life: Dorothy Hewett's Literary Criticism" (2010) JASAL Conference Issue

- Published plays at Currency Press

- Supple, A. The Man From Mukinupin Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Review of MTC performance, 2 April 2009

- Bon bons and roses for Dorothy on YouTube (1993), a documentary directed by Jackie McKimmie

External links

[edit] Media related to Dorothy Hewett at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dorothy Hewett at Wikimedia Commons- Hewett, Dorothy (1923–2002) at The Australian Women's Register

- Hewett, Dorothy (1923–2002) at The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

- 1923 births

- 2002 deaths

- Atheist feminists

- Australian women novelists

- Australian feminist writers

- Social realism

- Australian socialist feminists

- Deaths from breast cancer in Australia

- University of Western Australia alumni

- Writers from Perth, Western Australia

- Communist women writers

- Communist poets

- People from the Wheatbelt (Western Australia)

- People educated at Perth College (Western Australia)

- 20th-century Australian novelists

- 20th-century Australian dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Australian poets

- 20th-century Australian women writers

- Australian women poets

- Australian women dramatists and playwrights

- Members of the Order of Australia

- Communist Party of Australia members

- Expressionist dramatists and playwrights

- Australian women short story writers

- Academic staff of the University of Western Australia

- 20th-century Australian short story writers

- Writers from Sydney