Operation Pluto

Operation Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean or Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil, also written Operation PLUTO) was an operation by British engineers, oil companies and the British Armed Forces to build submarine oil pipelines under the English Channel to support Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy during the Second World War.

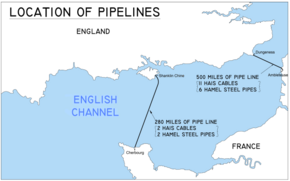

The British War Office estimated that petrol, oil, and lubricants would account for more than 60 per cent of the weight of supplies required by the expeditionary forces. Pipelines would reduce the need for coastal tankers, which could be hindered by bad weather, were subject to air attack, and needed to be offloaded into vulnerable storage tanks ashore. A new kind of pipeline was required that could be rapidly deployed. Two types were developed, named "Hais" and "Hamel" after their inventors. Two pipeline systems were laid, each connected by camouflaged pumping stations to the Avonmouth-Thames pipeline.

The first was the not-very-successful "Bambi" project, which connected Sandown on the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg in Normandy. Deployment of Bambi began on 12 August 1944, and it delivered just 3,300 long tons (3,400 t) between 22 September, when the first pipeline became operational, and 4 October, when it was terminated. More successful was "Dumbo", which ran from Dungeness on the Kent coast to Boulogne in Pas-de-Calais. The Dumbo system began pumping on 26 October, expanded to 17 pipelines by December, and remained in action until 7 August 1945. Ultimately, the pipelines carried about 8 per cent of all petroleum products sent from the United Kingdom to the Allied Expeditionary Force in North West Europe, including some 180 million imperial gallons (820 million litres) of petrol.

Background

[edit]In early April 1942, the Chief of Combined Operations, Vice-Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, approached the Secretary for Petroleum, Geoffrey Lloyd, and asked if an oil pipeline could be laid across the English Channel.[1] Mountbatten was tasked with planning the Allied invasion of German-occupied Europe, and had concerns about the supply of petroleum products, since it was considered unlikely that a port with oil reception facilities could be quickly secured.[2] The British War Office estimated that 60 per cent or more by weight of the supplies of the expeditionary forces would consist of petrol, oil and lubricants (POL).[3] In the initial stages of the assault, packaged fuel would be supplied in 20-litre (4.4-imperial-gallon) jerricans and 44-imperial-gallon (200-litre) drums. To supply the twenty million jerricans required, an entire American manufacturing plant was shipped to the London area, where it was operated by the Magnatex firm under the supervision of the Ministry of Supply.[1] By 1944, a stockpile of 250,000 long tons (250,000 t) of packaged petrol and diesel fuel had been accumulated in the UK.[4]

After the first few days of the invasion, it was hoped that petroleum could be supplied in bulk.[1] Pipelines were not the sole or even the principal means by which Combined Operations was contemplating supplying bulk petroleum; it intended to rely primarily on small shallow-draught coastal tankers, of which thirty were under construction.[5][6] American 600-deadweight-ton (610-deadweight-tonne) "Y" tankers began arriving in the UK in the spring of 1944. In 1943, the British also initiated a programme to construct 400-deadweight-ton (410-deadweight-tonne) Channel tankers (Chants), but only 37 were completed by May 1944.[7] It was hoped that petroleum products might also be supplied by ocean-going T2 tankers lying offshore through ship-to-shore pipelines. The project to develop these pipelines was codenamed Operation Tombola, and the pipelines themselves became known as Tombolas.[5] The submarine pipeline had sufficient advantages to make it worthwhile to explore as a backup means of supply. Submarine pipelines were less susceptible to enemy air attack and the frequently stormy English Channel weather, and their use would reduce the forces' dependency on vulnerable storage tanks ashore.[6]

Lloyd consulted his expert advisors: Brigadier Sir Donald Banks, the director-general of the Petroleum Warfare Department; Sir Arthur Charles Hearn, a former director of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and the oil advisor to the Fourth Sea Lord; and George Martin Lees, an eminent geologist.[8] At the time, submarine pipelines were in use in ports and over short distances, but no pipeline had ever been laid across such a great distance or under the currents and tidal conditions found in the English Channel. Moreover, to minimise interference by the enemy and the effect of the tides, the entire pipeline would have to be laid in a single night.[6] They regarded the proposal as infeasible using any known method of construction of pipelines 6 inches (15 cm) or more in diameter.[9]

The Chief Engineer of Anglo-Iranian, Clifford Hartley, was visiting the Petroleum Warfare Department at this time, and he heard about the proposal, and was convinced that it was possible.[8] In the hilly terrain of Iran, Anglo-Iranian had employed a 3-inch (7.6 cm) pipeline. Running at 1,500 psi (10,000 kPa), it delivered 100,000 imperial gallons (450,000 L) per day, the equivalent of over 20,000 jerricans. On 15 April he pitched his proposal for a continuous length of pipeline similar to a submarine communications cable without the core and insulation, but with armour to withstand the internal pressure, which could be deployed by a cable-layer ship. Additional capacity could be obtained by laying multiple lines.[9] By using high pressure, the line could carry different kinds of fuel. At low pressure different fuels would mix, but at high pressure they would stay separate. Thus, the pipeline could be used for aviation spirit, and then switched to diesel fuel.[10]

The project was given the codename Pluto, which stood for "pipeline underwater transportation of oil" or "pipeline under the ocean".[a] The operation was placed under the chief of staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, Designate (COSSAC). The G-4 section of the COSSAC staff, which assumed responsibility for Pluto, was headed by British Major General Nevil Brownjohn, with American Colonel F. L. Rash, Colonel Frank M. Albrecht, and Major General Robert W. Crawford successively as his deputy. Royal Navy Captain John Fenwick Hutchings from the Admiralty's Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development was placed in command of Operation Pluto. By VE-Day his command would consist of several ships, over 100 merchant navy officers and more than 1,000 men.[13]

Development

[edit]Hais

[edit]

Hartley received support for his proposal from the chairman of Anglo-Iranian, Sir William Fraser, who was also the petroleum advisor to the War Office, and from Henry Wright, the managing director of Siemens Brothers. Fraser agreed to pick up the costs of trials, albeit in the hope that the government would subsequently reimburse the company.[14][15] Siemens Brothers developed the cable in conjunction with the National Physical Laboratory based on their existing undersea telegraph cable. It was known as Hais, from Hartley-Anglo-Iranian-Siemens.[16]

The 2-inch (5 cm) diameter inner pipe, which would carry the petroleum, was made from extruded lead. This was surrounded by a layer of asphalt and paper impregnated with vinylite resin. Steel tape was wound around this to give it strength and flexibility. Around this was a layer of jute tape and asphalt-impregnated paper. Finally, it was covered by a protective layer of fifty galvanised steel wires, and camouflaged canvas cover. The pipe could deliver 3,500 imp gal (16,000 L) per day at a pressure of 500 psi (3,400 kPa), and withstand an underwater pressure of 1,950 psi (13,400 kPa).[15] The 2-inch size was chosen to keep the weight down; a larger cable would have required a larger ship to deploy it.[16]

A 120-yard (110 m) prototype was laid across the River Medway by the Post Office cable ship CS Alert on 10 May 1942. A pumping test was then carried out using pumps borrowed from the Manchester Ship Canal Company. After two days of pumping, a failure occurred. The cable was pulled up, and the problem was found to have been caused by extrusion of the lead through gaps in the steel tape. Accordingly, the amount of steel tape was increased from two to four layers.[15][17] At Siemens' suggestion, a second supplier, Henleys, was brought in to increase manufacturing capacity.[17] A second test was carried out in June across the Firth of Clyde, with lengths of pipe manufactured by both Siemens and Henleys. The pipe was laid by the Post Office cable ship Iris. Both functioned successfully.[18] Of the 710 nautical miles [nmi] (1,310 km) of Hais cable produced for the operation, 570 nmi (1,060 km) were made by firms in the United Kingdom, while 140 nmi (260 km) was manufactured in the United States by four American firms, including The Okonite Calendar Company, General Cable, Phelps Dodge and the General Electric Company.[19][20]

Full-scale production of the two-inch pipe was started on 14 August 1942, using steel from the Corby Steelworks, and on 30 October, 30 mi (50 km) of it was loaded on board HMS Holdfast under the command of Commander Henry Treby-Heale, which was to be used as a full-scale rehearsal of Operation Pluto.[21] This trial occurred on 29 December 1942. A 30-mile length was laid across the Bristol Channel in rough weather at a rate of 5 knots (9.3 km/h) with the shore ends being connected at Swansea and Ilfracombe. The sturdiness of the cable pipe was further tested when two German 500 lb (230 kg) bombs were dropped on Swansea 100 feet (30 m) from the cable. Later a ship's anchor dragged the cable pipe, but Holdfast was able to locate and repair the damage. To prove the reliability of the cable pipe, pumping operations were carried out continuously, first at the original design pressure of 750 psi (5,200 kPa), and then at 1,500 psi (10,000 kPa), with 56,000 imp gal (250,000 L) of fuel delivered per day.[22][23]

The trial was sufficiently successful that it was decided to develop 3-inch (7.6 cm)-diameter pipe. This reduced the number of pipelines required to pump the same volume of petrol, as each 3-inch pipe had more than twice the capacity of the 2-inch pipe. A merchant ship, HMS Algerian was acquired, and converted to carry 30 miles (48 km) of 3-inch cable pipe. Two more, the converted Liberty ships HMS Sancroft and HMS Latimer (later renamed Empire Baffin and Empire Ridley respectively) with a displacement of 12,220 long tons (12,420 t), could each handle 100 mi (160 km) of 3-inch pipe weighing approximately 6,400 long tons (6,500 t). Two storage tanks 50 feet (15 m) in diameter, one forward and one aft, provided the stowage space for the pipe.[24][25] Thames barges were converted to handle connecting the cable at the shore ends, where the waters were too shallow for these ships to operate.[26] These were HM cable barges Britannic, Oceanic, Runic, Gold Dust and Gold Drift. Each was 90 feet (27 m) long with a 20-foot (6.1 m) beam and a loaded displacement of 450 long tons (460 t) carrying 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of three-inch Hais pipe.[25]

Anglo-Iranian Oil personnel supervised the erection of pumping equipment by the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), Pioneer Corps and Royal Engineers personnel, and a RASC bulk petroleum company was specially trained to operate them.[24][25] A Port of London Authority factory at Tilbury was requisitioned and converted into a cable pipe factory where 3 to 4 nmi (5.6 to 7.4 km) of cable pipe per day was tested, welded into 4,000-foot (1,200 m) lengths and stored.[22]

Hamel

[edit]

Lead was in short supply, so the Petroleum Warfare Department decided to seek an alternative that made use of cheaper and more readily available materials as a backup system to Hais, which was itself a backup system. Bernard J. Ellis, the chief engineer of the Burmah Oil Company, was convinced that a flexible pipeline could be built from mild steel, which was more readily available than lead. His pipe was 3+1⁄2 in (8.9 cm) in diameter, with 0.212-inch (5.4 mm) walls.[27]

The prototype was fabricated in 30-foot (9.1 m) segments by J & E Hall, a firm better known as a manufacturer of refrigeration equipment. The segments were made to be flash welded together. Normally welded pipe gave trouble due to rings of residue that formed around each weld. Ellis designed a special broaching tool to remove the metal swarf. Ellis teamed with H. A. Hammick, the chief engineer of Iraq Petroleum Company, and the pipe became known as 'Hamel' after their surnames, although after the war Ellis successfully asserted his claim to be recognised as the sole inventor.[27]

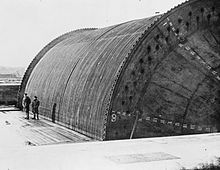

Unlike Hais, Hamel pipe was too stiff to be coiled in a ship's hold, as it could not withstand the twist along the longitudinal axis that came with each turn of the coil.[27][28] The Petroleum Warfare Department proposed that it be wound around a buoyant steel drum that could be towed by tugs or fitted on a Hopper barge.[16] The resulting steel drum was 60 ft (18 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) in diameter,[27] and was known as a "Conun" or "Conundrum". Tests were carried out in the Froude tank at the National Physical Laboratory to verify that Conundrums could be towed at speed without yawing.[28]

Stewarts & Lloyds undertook to design, construct and operate two factories at Tilbury where 40-foot (12 m) lengths of pipe were welded together into 4,000-foot (1,200 m) segments. Six Conundrums were constructed at a cost of £30,000 apiece, and named HMS Conundrum 1 through 6. A Conundrum was towed to a special dock where it was held by two steel arms. A sprocket chain driven by an electric motor rotated the Conundrum while pipe was wound around it. At the end of each 4,000-foot (1,200 m) segment, the next was welded, the swarf was cleaned out, and the process continued until the Conundrum held 90 miles (140 km) of pipe, at which point it had a displacement of 1,600 long tons (1,600 t).[29][25]

An Admiralty hopper barge named W.24 was converted to carry a Conundrum, and named HMS Persephone.[29] It was a twin-screw vessel 200-foot (61 m) and 35-foot (11 m) wide. On 4 June 1943 a trial lay of one mile of Hamel pipe was successfully carried out. Though not having the capacity to cross the Channel, Persephone laid 16 Hamel pipes across the Solent to the Isle of Wight.[30][25] It was not known precisely how long the Hamel pipe would last, but it was assumed to be about six weeks. Fluorescein dye was added to the fuel to allow patrol aircraft to detect leaks.[27][28] In view of this success, it was decided to utilise both Hais and Hamel.[4]

Pumping stations

[edit]

In the spring of 1943, the Petroleum Warfare Department selected sites for the pumping stations. One was established at Sandown on the Isle of Wight, and another at Dungeness on the Kent coast. Construction was carried out at night and in secret, and equipment was carried in under tarpaulins. The pumping stations and storage tanks were camouflaged to look like villas, seaside cottages, old forts, amusement parks and other innocuous features. Strict instructions were issued that neither "Petroleum Warfare Department" nor its initials should appear on any letter or package. The locations were erased from maps. Lorry drivers conducting deliveries had to phone from a public phone booth for instructions.[31]

Each pumping station was equipped with thirty diesel-powered reciprocating pumps with a capacity of 180 long tons (180 t) per day, and four large Byron Jackson Company electric centrifugal pumps capable of 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) per day, which worked out to 400,000 imperial gallons (1,800,000 L) at 1,500 psi (10,000 kPa).[31][32] Both stations were fed from the Avonmouth-Thames pipeline, which had a capacity of 135,000 long tons (137,000 t) per month. A 70-mile (110 km) branch line was constructed connecting Dungeness with its eastern terminal at Walton-on-Thames. Sandown was connected to the system through a 22-mile (35 km) link between the Isle of Wight and Fawley Refinery. The pipeline connections to Pluto were completed by March 1944.[4]

The corresponding sites in France were selected in June 1943.[31] Sandown would be connected to the port of Cherbourg, a distance of over 65 nmi (120 km). Dungeness would be connected to the port of Ambleteuse.[33] In keeping with the Disney theme suggested by Pluto, the former was codenamed "Bambi" and the latter "Dumbo".[31]

As part of the Operation Overlord deception operation known as Operation Fortitude, a fake oil dock was created at Dover. The architect Basil Spence was called upon to design it. Constructed from camouflaged scaffolding, fibreboard and old sewage pipe, the fake facility spanned 3 acres (1.2 ha) and included fake versions of pipelines, storage tanks, jetties, vehicle parks and antiaircraft emplacements. Wind machines were used to create clouds of dust to simulate activity, and the site was guarded by the military police. At night it was obscured by a smoke screen. German aircraft were allowed to overfly the facility, but only above 33,000 feet (10,000 m), where high-resolution imagery was not possible. The fake facility was inspected by King George VI, and the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his ground forces commander, General Sir Bernard Montgomery spoke to the "workers".[34]

Placement

[edit]Bambi

[edit]According to the original Operation Overlord plan, Cherbourg was supposed to be captured within eight days of D-Day (D+8) and, despite the expectation that the Germans would carry out systematic demolitions, be opened within three days.[35] Pipe laying was to commence four days later,[36] with the Bambi system fully operational by D+75 (seventy-five days after D-Day).[37] The discovery of an additional German division in the vicinity in May led to the expected capture being pushed back ten days from D+8 to D+18.[38] In the event, the port of Cherbourg was captured on 27 June (D+21),[39] and due to the extensive damage the first POL tanker did not discharge there until 25 July (D+49).[40] In the meantime, fuel was supplied through the small port of Port-en-Bessin by coastal tankers, and from ocean-going tankers using two Tombola lines at Port-en-Bessin for the British and five at Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes for the Americans. The Tombola lines had a tendency to break, and the Chants fared poorly in the rough weather of the English Channel. By 28 July sixteen of them were laid up for repairs at a special tanker repair facility that had been established at Hamble-le-Rice.[37]

Consideration was given to cancelling Pluto, but under the circumstances it was decided to proceed.[41] Time was wasted in deciding whether to terminate the line inside or outside the harbour; eventually the latter was chosen. The first Hais pipeline was laid by HMS Latimer in just ten hours on 12 August 1944, but the pipeline failed when an escorting destroyer caught it with its anchor and damaged it beyond repair. A second effort was made by HMS Sancroft two days later. This too failed when the pipe became wrapped around the propeller of the support ship, HMS Algerian. An attempt to lay Hamel pipe instead failed on 27 August when it was discovered that tons of barnacles had attached themselves to the bottom of HMS Conundrum 1, thereby preventing it from rotating. The barnacles were scraped off, and another attempt was made a few days later, but the pipeline broke about 29 nmi (54 km) out.[42]

The expert technicians had been able to lay pipelines across the Bristol Channel and the Solent under the supervision of the designers, but it was another matter for the naval laying parties to achieve the same degree of proficiency under wartime conditions and across the much wider English Channel.[43] Sir Donald Banks wrote: "The technique of cable laying had been mastered but we were not yet sufficiently versed in the practice of connecting the shore ends, nor in effecting repairs to the undersea leaks which were caused fairly close inshore through these faulty concluding operations."[44]

Finally, on 22 September a Hais cable was laid that worked, delivering 56,000 imperial gallons (250,000 L) per day. This was followed on 29 September by the successful installation of a Hamel cable by HMS Conundrum 2.[42] However, on 3 October when the pressure was increased from 50 to 70 bars (730 to 1,020 psi) to augment the amount of fuel pumped,[41] both pipelines failed: the Hais due to a faulty coupling, and the Hamel when it encountered a sharp edge on the ocean floor.[42] Operation Bambi was terminated the following day. Only about 3,300 long tons (3,400 t) (935,000 imperial gallons (4,250,000 L)) of fuel had been transferred.[37][26]

Dumbo

[edit]

Meanwhile, the port of Rouen had been captured on 30 August, and Le Havre on 12 September. Le Havre was badly damaged in the fighting and by demolitions.[45] Rouen, an inland port 75 miles (121 km) up the Seine River,[46] was in better shape, with its quays largely intact, although demolitions had been carried out and the river channel to it was blocked by mines and sunken vessels. Even when it was cleared the channel from Le Havre was shallow, but coastal tankers carrying POL from the UK were able to navigate it and discharge in Rouen.[45] Boulogne was captured on 22 September, and the port was opened on 22 October.[47]

A Hais pipeline was laid by HMS Sancroft, which commenced pumping on 26 October, and remained in action until the end of the war.[48] Lines were run to a beach in the outer harbour of Boulogne, 23 nmi (43 km) distant across the Strait of Dover,[49] instead of Ambleteuse as originally planned because the beach at the latter was heavily mined. This involved a longer distance and a more difficult approach, but cable-laying techniques had been refined. The ends of the cable were dropped just offshore and picked up by the barges for connection to the shore. The Hamel pipe gave more trouble, but after some trial and error, it was laid with sections of Hais pipe at each end.[33] Boulogne also had poor railway facilities, so the pipeline was extended to Calais where better railway connections were available to transport the fuel. This extension was completed in November.[50]

By December, nine 3-inch and two 2-inch Hamel pipelines and four 3-inch and two 2-inch Hais cable pipelines had been laid, a total of 17 pipelines,[48][51] and Dumbo was providing 1,300 long tons (1,300 t) of petrol per day.[50] Not one of the Hais cable pipelines broke, and the mean time between repairs of the Hamel pipelines varied between 52 and 112 days, with 68 days being the average. They could not be run at the intended pressure, so they carried only petrol, and plans for the pipelines to deliver aviation spirit as well were discarded.[48][51]

In December there was reconsideration of whether to continue with Operation Pluto. By this time Antwerp was unloading an ocean-going tanker a day, and coastal tankers were delivering 2,500 to 3,000 long tons (2,500 to 3,000 t) per day to Ostend, and a similar amount to Rouen. On the other hand, only Antwerp and Cherbourg were capable of handling the large tankers, but Antwerp was under attack from V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets, and it was considered inadvisable for it handle more than one tanker at a time. As for the coastal tankers, they were in demand for service in the Far East. It was therefore decided to continue with Operation Pluto.[51]

As the fighting moved on to Germany, Dumbo was connected to an inland pipeline system that was extended from Boulogne to Antwerp, Eindhoven and ultimately Emmerich. Dumbo surpassed its target of 1 million imperial gallons (4.5 million litres) (about 3,000 long tons (3,000 t)) per day on 15 March 1945, and by 3 April the Dumbo lines were delivering 4,500 long tons (4,600 t) a day to the Rhine.[48] New lines continued to be laid, the last one being laid on 24 May.[43]

The system was finally closed down to save manpower on 7 August, by which time the pipelines had carried 180 million imperial gallons (820 million litres) of petrol. Operation Pluto was officially disbanded on 31 August, and the Petroleum Warfare Department was wound up on 31 March 1946. The Tilbury plant was transferred to the Admiralty, and all remaining stores to the Ministry of Supply. No post-war use of the technology was contemplated, so Operation Pluto's records were sent to the Public Record Office, where they remained sealed for the next thirty years.[52] The Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors awarded tax-free payments of £9,000 to Hartley; £5,000 to Ellis; £85 to M. K. Purvis, the designer of the Conundrum; and £250 to A. E. Price, who designed the wedge gripping device used to fix the pipeline near the shore.[53]

It is estimated that nearly 5.4 million long tons (5.5 million tonnes) of petroleum products were delivered to the Allied Expeditionary Force. Of this, 826 thousand long tons (839 thousand tonnes) came directly from the United States and 4.3 million long tons (4.4 million tonnes) (84 per cent) from the United Kingdom, of which Operation Pluto contributed 370 thousand long tons (380 thousand tonnes) or 8 per cent.[51] The total cost of Operation Pluto was reckoned at £4,428,000.[52]

Recovery and salvage

[edit]| Pluto power station in the pavilion at Browns golf course | |

|---|---|

The pumping station at Sandown, originally disguised as Brown's Ice Cream | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Sandown |

| Country | England |

| Grid position | SZ 60592 85013 |

| Completed | 1944 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 9 August 2006 |

| Reference no. | 1391723 |

After the war, more than 85 per cent of the pipeline was salvaged and subsequently scrapped. This was accomplished during the period September 1946 to October 1949, using Latimer and Holdfast (by then operated by Ministry of War Transport under the names Empire Ridley and Empire Taw), Empire Tigness (a former German tanker), Wrangler (an ex-Admiralty Mark III tank landing craft), and Redeemer (an ex-Admiralty motor fishing vessel).[54]

In all, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of the original 23,000 long tons (23,000 t) of lead and 3,300 long tons (3,400 t) of the original 5,500 long tons (5,600 t) of steel were recovered, along with 75,000 imperial gallons (340,000 L) of petrol that were still in the pipelines.[53] The value of the scrap lead and steel was well in excess of the costs of recovery.[54] The total value of the salvaged steel and lead was estimated at £400,000.[55]

Although the pipeline itself is no longer in use, many of the buildings that were constructed or utilised to disguise it remain, especially on the Isle of Wight, where the former pumping station at Sandown is currently in use as a miniature golf facility.[56]

Historiography

[edit]The value of Operation Pluto was controversial. Samuel Eliot Morison, the United States naval historian, noted that the pipelines "proved very useful for supplying the Allied armies as they advanced in Germany."[57] According to the civil official historian, Michael Postan, Operation Pluto was "strategically important, tactically adventurous, and, from the industrial point of view, strenuous".[58] On 24 May 1945, Winston Churchill described Operation Pluto as "a wholly British achievement and a piece of amphibious engineering skill of which we may well be proud."[59]

A contrary view was expressed by Derek Payton-Smith in the civil official history volume on oil: "Pluto contributed nothing to Allied supplies at a time that would have been most valuable—that is, when no regular oil ports were available on the Continent and the Allies were relying on the unsatisfactory Port-en-Bessin. Dumbo was more successful, but at a time when success was of less importance."[43] A similar sentiment was expressed by Major-General Sir Frederick Morgan, the head of the COSSAC staff, who considered that Bambi was not worthwhile, although he lauded Dumbo.[60]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The British official History of the Second World War Civil Series volume Oil gives "Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil"[6] but the Military Series volume Victory in the West gives "Pipe Lines Under the Ocean",[11] and the Army Series volume Maintenance in the Field says "pipeline under the ocean".[12]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Krammer 1992, p. 443.

- ^ Whittle 2013, p. 202.

- ^ Krammer 1992, p. 442.

- ^ a b c Payton-Smith 1971, pp. 410–411.

- ^ a b Krammer 1992, p. 447.

- ^ a b c d Payton-Smith 1971, p. 334.

- ^ Payton-Smith 1971, pp. 411–412.

- ^ a b Krammer 1992, p. 444.

- ^ a b Hartley 1945, p. 23.

- ^ Krammer 1992, pp. 444–446.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, p. 134.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 259.

- ^ Krammer 1992, p. 446.

- ^ Hartley 1945, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Krammer 1992, pp. 447–448.

- ^ a b c Payton-Smith 1971, p. 335.

- ^ a b Hartley 1945, p. 24.

- ^ Hartley 1945, p. 25.

- ^ Postan 1952, p. 279.

- ^ "PLUTO – The Undersea Pipe Line". Popular Science. Vol. 147, no. 2. August 1945. pp. 62–64.

- ^ "PLUTO - Pipe-lines Under the Ocean". Kent Past. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ a b Krammer 1992, pp. 449–451.

- ^ Hartley 1945, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Hartley 1945, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e Moore 1954, p. 616.

- ^ a b Carter & Kann 1961, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d e Krammer 1992, pp. 451–453.

- ^ a b c Hartley 1945, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Colledge 1969, p. 274.

- ^ Glover, Bill (2012). "HMS Persephone". Atlantic Cable. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Krammer 1992, pp. 454–455.

- ^ Hartley 1945, p. 30.

- ^ a b Hartley 1945, p. 31.

- ^ Krammer 1992, pp. 455–457.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, pp. 288–292.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Payton-Smith 1971, p. 446.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, p. 297.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, p. 427.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1953, p. 501.

- ^ a b Whittle 2013, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Krammer 1992, p. 460.

- ^ a b c Payton-Smith 1971, p. 448.

- ^ Banks 1946, p. 197.

- ^ a b Beck et al. 1985, p. 360.

- ^ Ruppenthal 1959, p. 102.

- ^ Ellis & Warhurst 1968, pp. 60–63.

- ^ a b c d Krammer 1992, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 260.

- ^ a b 21st Army Group 1945, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Payton-Smith 1971, p. 447.

- ^ a b Krammer 1992, pp. 462–463.

- ^ a b "£15,100 for 'Pluto' Inventors: Pipelines Carried 200,000,000 Gallons Of Petrol". The Manchester Guardian. 16 August 1949. p. 6 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Pluto: The Salvage Operation – 1947 to 1949". Combined Ops. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Pluto Pipeline (Salvage)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 450. House of Commons. 13 May 1948.

- ^ "PLUTO power station in the pavilion at Browns golf course". Historic England. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Morison 1957, p. 218.

- ^ Postan 1952, p. 278.

- ^ Krammer 1992, p. 464.

- ^ Morgan 1950, pp. 266–267.

References

[edit]- 21st Army Group (November 1945). The Administrative History of the Operations of 21 Army Group on the Continent of Europe 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945. Germany: 21st Army Group. OCLC 911257199.

- Banks, Donald (1946). Flame Over Britain: A Personal Narrative of Petroleum Warfare. Sampson Low, Marston and Co. OCLC 799365221.

- Beck, Alfred M.; Bortz, Abe; Lynch, Charles W.; Mayo, Lida; Weld, Ralph F. (1985). The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Germany (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The Technical Services. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 40485571. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- Carter, J. A. H.; Kann, D. N. (1961). Maintenance in the Field, Volume II: 1943–1945. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 1109671836.

- Colledge, J. J. (1969). Ships of the Royal Navy: An Historical Index. Vol. 2. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4396-8. OCLC 81267.

- Ellis, L. F.; Warhurst, A. E. (1968). Victory in the West – Volume II: The Defeat of Germany. History of the Second World War. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 758329926.

- Hartley, A. C. (7 December 1945). "Operation Pluto". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 94 (4706): 23–34. ISSN 0035-9114. JSTOR 41362941.

- Krammer, Arnold (July 1992). "Operation PLUTO: A Wartime Partnership for Petroleum". Technology and Culture. 33 (3): 441–466. doi:10.2307/3106633. ISSN 1097-3729. JSTOR 3106633. S2CID 112426992.

- Moore, Rufus J. (June 1954). "Operation Pluto". Proceedings. 80 (6): 616. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- Morgan, Frederick (1950). Overture to Overlord. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 638838921.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1957). The Invasion of France and Germany. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XI. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 671874345.

- Payton-Smith, Derek Joseph (1971). Oil—A Study of War-time Policy and Administration. History of the Second World War. HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630074-4. OCLC 185469657.

- Postan, Michael (1952). British War Production. History of the Second World War. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 1067443504.

- Ruppenthal, Roland G. (1953). Logistical Support of the Armies (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The European Theater of Operations. Vol. I, May 1941 – September 1944. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 640653201.

- Ruppenthal, Roland G. (1959). Logistical Support of the Armies (PDF). United States Army in World War II – The European Theater of Operations. Vol. II, September 1944 – May 1945. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 8743709. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Whittle, Tim (September 2013). "Pigs, Pipelines and PLUTO: A History of the United Kingdom's Largest Oil Pipeline and Storage System during World War Two". Measurement and Control. 46 (7): 199–204. doi:10.1177/0020294013499112. ISSN 0142-3312. S2CID 109078213.

Further reading

[edit]- Brooks, C. (1950). The History of Johnson and Phillips: A Romance of Seventy-Five Years'. Johnson & Phillips. OCLC 30161439.

- Hartley, A.C. (March 1947). "Operation Pluto". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 154 (4): 433–438. doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1946_154_054_02.

- Scott, J.D (1958). Siemens Brothers, 1858-1958: An Essay in the History of Industry. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. OCLC 1229809756.

- Searle, Adrian (2004). PLUTO: Pipe-line Under the Ocean (2nd ed.). Shanklin, Isle of Wight: Shanklin Chine. ISBN 0-9525876-0-2. OCLC 56103645.

- Smith, Tim (May–June 2019). "PLUTO - Pipe Line Under The Ocean". Steel Times International. 43 (4): 116. ProQuest 2298149745 – via ProQuest.

- Taylor, W. Brian (2004). "PLUTO—Pipeline under the Ocean". The Quarterly Journal for British Industrial and Transport History. 42: 48–64. ISSN 1352-7991.

- Whittle, Tim (2017). Fuelling the Wars: PLUTO and the Secret Pipeline Network. Folly Books. ISBN 978-0-9928554-6-8.

External links

[edit]- Detailed film about Pluto (silent). IWM. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- "Pipe laying operations". Combined Ops. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- Operation Pluto. British Pathé. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- 1944 in military history

- 1945 in military history

- 1944 in the United Kingdom

- 1945 in the United Kingdom

- Anglo-Persian Oil Company

- British inventions

- Military logistics of World War II

- Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Oil pipelines in the United Kingdom

- Operation Overlord

- Western European Campaign (1944–1945)

- Lord Mountbatten

- World War II in the English Channel

- Allied logistics in the Western European Campaign (1944–1945)