Sutler

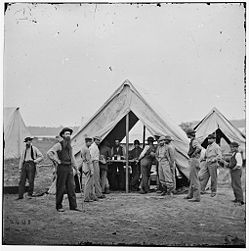

A sutler or victualer is a civilian merchant who sells provisions to an army in the field, in camp, or in quarters. Sutlers sold wares from the back of a wagon or a temporary tent, traveling with an army or to remote military outposts.[1] Sutler wagons were associated with the military, while chuckwagons served a similar purpose for civilian wagon trains and outposts.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word came into English from Dutch, where it appears as soetelaar or zoetelaar. It meant originally "one who does dirty work, a drudge, a scullion," and derives from zoetelen (to foul, sully; modern Dutch bezoedelen), a word cognate with "suds" (hot soapy water), "seethe" (to boil) and "sodden".

Role in supplying troops

[edit]These merchants often followed the armies during the French and Indian War, American Revolution, American Civil War, and the Indian Wars, to sell their merchandise to soldiers. Generally, the sutlers built their stores within the limits of an army post or just off the defense line, and needed to receive a license from the Commander prior to construction. They were, by extension, also subject to his regulations. They frequently operated near the front lines and their work could be dangerous; at least one sutler was killed by a stray bullet during the Civil War. A typical transaction with a sutler is dramatized in the third chapter of MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Andersonville (1955).

Sutlers, frequently the only local suppliers of non-military goods, often developed monopolies on critical commodities like alcohol, tobacco, coffee, or sugar and rose to powerful stature. Since government-issued coinage was scarce during the Civil War, sutlers often conducted transactions using a particular type of Civil War token known as a sutler token.[3]

Sutlers played a major role in the recreation of army men between 1865 and 1890. Sutlers' stores outside of military posts were usually also open to non-military travelers and offered gambling, drinking, and prostitution.

In modern use, sutler often describes businesses that provide period uniforms and supplies to reenactors, especially to American Civil War reenactors. These businesses often play the part of historical sutlers while selling both period and modern-day goods at reenactments.

Honourable Artillery Company

[edit]The Honourable Artillery Company, a regiment of the British Army, still uses the word "sutling" as an alternative to the more common "mess" or "messing". Due to the unique culture of the regiment, no social differentiation is made between officers and other ranks, and therefore the regiment does not have separate drinking and dining facilities for officers, warrant officers, sergeants or other ranks. A room in the headquarters of the regiment in the City of London is called the "Sutling Room", and it contains the main bar where all ranks meet and socialise.[4] Often, when the regiment is deployed, a room, tent, or vehicle will be designated as the Sutling Room, Sutling Tent or Sutling Lorry, and will perform the same function.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Delo, David Michael (1998). Peddlers and Post Traders: The Army Sutler on the Frontier. Larousse Kingfisher Chambers. ISBN 0-9662218-1-8.

- ^ Tangires, Helen (Summer 1990). "American Lunch Wagons". Journal of American Culture. 13 (2): 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734x.1990.1302_91.x.

- ^ "Civil War 25-Cent Sutler Token: How Sutler Coins Were Used". Shapell Manuscript Foundation. SMF.

- ^ "Company".

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sutler". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 171.

- Lord, Francis A. (1969). Civil War Sutlers and Their Wares. T. Yoseloff. ISBN 0-498-06805-6.

- Butler, Anne M. (1987). Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery: Prostitutes in the American West, 1865–90, University of Illinois Press, 137–139. ISBN 0-252-01466-9.