Eagle Rock, Los Angeles

34°08′20″N 118°12′47″W / 34.13889°N 118.21306°W

Eagle Rock | |

|---|---|

|

Top: historic Women's Temperence Union building (left), Occidental College (right); bottom: Eagle Rock (left), St. Dominic Catholic Church (right). | |

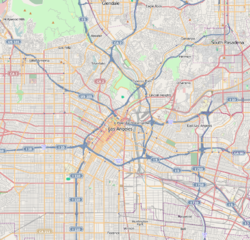

Map of the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles as delineated by the Los Angeles Times | |

| Coordinates: 34°08′20″N 118°12′47″W / 34.13889°N 118.21306°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| City | |

| Government | |

| • U.S. House | Jimmy Gomez (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.0 km2 (4.25 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 173 m (568 ft) |

| Population (2008)[1] | |

| • Total | 34,644 |

| • Density | 3,100/km2 (8,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Zip codes | 90041, 90042, 90065 |

| Area code(s) | 213, 323 |

Eagle Rock is a neighborhood of Northeast Los Angeles, abutting the San Rafael Hills in Los Angeles County, California. The community is named after Eagle Rock, a large boulder whose shadow resembles an eagle.[3] Eagle Rock was once part of the Rancho San Rafael under Spanish and Mexican governorship. In 1911, Eagle Rock was incorporated as a city, and in 1923 it was annexed by Los Angeles.

The neighborhood is the home of Occidental College. As with other neighborhoods in Northeast Los Angeles, Eagle Rock experienced significant gentrification in the 21st century.[4]

History

[edit]

Before the arrival of European settlers, the secluded valley below the San Rafael Hills that is roughly congruent to Eagle Rock's present boundaries was inhabited by the Tongva people, whose staple food was the acorns from the valley's many oak trees.[3][5] These aboriginal inhabitants were displaced by Spanish settlers in the late 18th century, with the area incorporated into the Rancho San Rafael.[5] Following court battles, the area known as Rancho San Rafael was divided into 31 parcels in 1870. Benjamin Dreyfus was awarded what is now called Eagle Rock.[5] In the 1880s Eagle Rock existed as a farming community.

The arrival of American settlers and the growth of Los Angeles resulted in steadily increasing semi-rural development in the region throughout the late 19th century. The construction of Henry Huntington's Los Angeles Railway trolley line up Eagle Rock Boulevard to Colorado Boulevard and on Colorado to Townsend Avenue commenced the rapid suburbanization of the Eagle Rock Valley.

Although Eagle Rock, which is geographically located between the cities of Pasadena and Glendale, was once incorporated as a city in 1911, its need for an adequate water supply and a high school resulted in its annexation by Los Angeles in 1923.[6]

Several major crime sprees occurred in the neighborhood during the late 20th century. An early victim of the Hillside Strangler was discovered in an Eagle Rock neighborhood on October 31, 1977. The discovery, along with the successive murders of at least 10 other women in the area over the course of five months, frightened local residents. According to an opinion piece by a resident under the pseudonym Deirdre Blackstone that was published in the Los Angeles Times on December 6, 1977:

Groups of gum-chewing girls in look-alike hairdos and jeans who used to haunt the Eagle Rock Plaza—they too are keeping close to home ... We are all afraid. For women living alone, ours is an actual visceral fear that starts at the feet. Then it hits the knees—and finally it grips the mind.[citation needed]

Two men, Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono, were subsequently convicted of the murders.

On the night of March 20, 1985, an 8-year-old girl was abducted from her home in Eagle Rock and sexually assaulted by a man dubbed the "Valley Intruder", "Walk-in Killer", and "The Night Stalker," later identified as Richard Ramirez. This was the seventh in a long string of murders and sexual assaults committed by Ramirez in Los Angeles and San Francisco before he was apprehended.[7]

In 2002, an effort to designate an area of the community as "Philippine Village" for the large Filipino American population was stopped.[8]

Like the surrounding areas of Northeast Los Angeles, Eagle Rock has undergone gentrification. Beginning in the 2000s, the area attracted young professionals and fostered a hipster culture.[9][10] As a result, housing prices have dramatically risen and a new wave of restaurants, coffee shops, bars, and art galleries have appeared over the last decade.

Demographics

[edit]

The neighborhood is inhabited by a wide variety of ethnic and socioeconomic groups and the creative class.[3][5] Over the past decade the Eagle Rock and neighboring Highland Park have been experiencing gentrification as young professionals have moved from nearby neighborhoods such as Los Feliz and Silver Lake.[5] A core of counter-culture writers, artists and filmmakers has existed in Eagle Rock since the 1920s.[5]

According to the "Mapping L.A." project of the Los Angeles Times, the 2000 U.S. census counted 32,493 residents in 4.25 sq mi (11.0 km2) Eagle Rock neighborhood, 7,644 people per square mile; a population density considered average for the city and Los Angeles County. In 2008, the city estimated that the population had increased to 34,466. In 2000, the median age for residents was 35, about average for city and county neighborhoods.[1]

The neighborhood was considered "highly diverse" ethnically within Los Angeles, with a relatively high percentage of Asian people. The breakdown was Latinos, 40.3%; whites, 29.8%; Asians, 23.9%; blacks, 1.8%; and others, 4.1%. The Philippines (35.1%) and Mexico (25.1%) were the most common places of birth for the 38.5% of the residents who were born abroad—an average figure for Los Angeles.[1]

The median yearly household income in 2008 dollars was $67,253, considered high for the city. The neighborhood's income levels, like its ethnic composition, can still be marked by notable diversity, but typically ranges from lower-middle to upper-middle class.[11] Renters occupied 43.9% of the housing stock, and house- or apartment-owners held 56.1%. The average household size of 2.8 people was considered normal for Los Angeles.[1]

Thirty percent of Eagle Rock residents aged 25 and older had earned a four-year degree by 2000, an average percentage for the city.[1]

Geography

[edit]Eagle Rock is bordered by Glendale on the north and west, Highland Park on the southeast, Glassell Park on the southwest, and Pasadena on the east. Major thoroughfares include Eagle Rock Boulevard and Colorado Boulevard, with Figueroa Street along the eastern boundary. The Glendale and Ventura freeways run along the district's western and northern edges, respectively.

Landmarks

[edit]

The neighborhood is home to many historic and architecturally significant homes, many done in the Craftsman,[3] Georgian, Streamline Moderne,[5] Art Deco and Mission Revival styles.[3] There are nine Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in Eagle Rock:

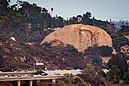

- The Eagle Rock - located at the terminus of Figueroa Street, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #10.

- Eagle Rock City Hall - Located at 2035 Colorado Boulevard, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #59. Once a separate municipality, this was Eagle Rock's original City Hall.[12]

- Eagle Rock Branch Library - Located at 2225 Colorado Boulevard, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #292. The original library, which was built with the aid of a Carnegie grant in 1914, was replaced in 1927 with a new structure which used one wall and the basement of the old library. It now serves as the Center for the Arts Eagle Rock.[13]

- Residence at 1203-1207 Kipling Avenue - It is Historic-Cultural Monument #383.

- Loleta House - Located on Loleta Avenue, it is a cultural hub and home to the Loleta Boys.

- Argus Court - Located at 1760-1768 Colorado Boulevard, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #471.

- Eagle Rock Playground Clubhouse - Located at 1100 Eagle Vista Drive , it is Historic-Cultural Monument #536.

- Eagle Rock Women's Twentieth Century Clubhouse - Located at 1841-1855 Colorado Boulevard, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #537.

- Swanson House - Located at 2373 Addison Way, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #542.

- Eagle Rock Women's Christian Temperence Union Home - Located at 2222-2244 Laverna Avenue & 2225-2245 Norwalk Avenue, it is Historic-Cultural Monument #562.

The Bucket is a historic example of programmatic or novelty architecture meant to look live a 1930s ice chest and usually used as hamburger stand.[14]

Parks and recreation

[edit]- Eagle Rock Recreation Center - 1100 Eagle Vista Dr., Los Angeles, CA 90041[15]

- Eagle Rock Dog Park - 1100 Eagle Vista Drive Los Angeles, CA 90041.[16]

- Eagle Rock Hillside Park - North of the Ventura Freeway and South of Valle Vista, Los Angeles, CA 90041.[17]

- Richard Alatorre Park - Figueroa and 134 Freeway, Los Angeles, CA 90041.[18]

- Yosemite Recreation Center - 1840 Yosemite Dr., Los Angeles, CA 90041.[19]

Education

[edit]

Higher education

[edit]Eagle Rock is the site of Occidental College, which was first established in Boyle Heights in 1887. After a fire destroyed the original campus in 1896, it moved to Downtown Los Angeles, then Highland Park, until reopening permanently in Eagle Rock in 1914. The campus was designed by architect Myron Hunt.[20][21]

Schools

[edit]Eagle Rock children attend schools in District 4[22] of the Los Angeles Unified School District.[23]

- Eagle Rock High School, 1750 Yosemite Drive. Eagle Rock High School was built in 1927 by the city of Los Angeles, as promised at the time of Eagle Rock's annexation. The original building was demolished in 1970 over concerns about its earthquake safety. It was replaced by a contemporary brutalist style building at the rear of the same school site.[13]

- Renaissance Arts Academy, charter high school, 1800 Colorado Boulevard

- Dahlia Heights Elementary School, 5063 Floristan Avenue

- Santa Rosa Charter Academy, middle school, 3838 Eagle Rock Boulevard

- Eagle Rock Elementary School, 2057 Fair Park Avenue

- Rockdale Elementary School, 1303 Yosemite Drive

- Delevan Drive Elementary School, 4168 West Avenue 42

- Toland Way Elementary School, 4545 Toland Way

- Annandale Elementary School, 6125 Poppy Peak Drive

- Celerity Rolas Charter School, 1495 Colorado Boulevard. Closed for 2018–2019 school year.[24]

Notable residents

[edit]- Ben Affleck, a former Occidental College student, lived on Hill Drive with then-roommate and co-writer Matt Damon while they wrote the script for Good Will Hunting'.[25]

- Maria Bamford (comedian)[26]

- Marlon Brando (actor)[27][28]

- Mike Carter (American-Israeli basketball player)

- John Dwyer (musician)[29]

- Zack de la Rocha (musician)[30]

- Paul Ecke (botanicals)[27]

- M.F.K. Fisher (writer)[31]

- Lloy Galpin (suffragist, teacher)[32]

- Jack Kemp (Congressman, quarterback, HUD Secretary - Occidental College alumnus)

- Terry Jennings (Early Minimalist Composer and Jazz pioneer)

- Carlos R. Moreno (jurist)[27]

- Barack Obama (44th President of the United States - Occidental College student)

- Zasu Pitts (actress)[27]

- Hanson Puthuff (artist)[27]

- Mark Ryden (artist)[33]

- Robert Shaw (conductor)[27]

- John Steinbeck (author)[34]

- Madeleine Stowe (actress)[35]

- Bill Tom (Olympic gymnast)[36]

- Marshall Thompson (actor)[27]

- Dalton Trumbo (screenwriter, author)[27]

- Lindsay Wagner (actress)[37]

- Virginia Weidler (actress)[38]

- Keith Wyatt (Musician, educator)[27]

See also

[edit]- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments on the East and Northeast Side

- List of districts and neighborhoods in Los Angeles

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f http://projects.latimes.com/mapping-la/neighborhoods/neighborhood/eagle-rock "Eagle Rock," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Worldwide Elevation Finder".

- ^ a b c d e http://www.eaglerockcouncil.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=60&Itemid=72 Eagle Rock Neighborhood Council, History of. Retrieved June 24, 2010

- ^ Lin, Jan (June 4, 2015). "Northeast Los Angeles Gentrification in Comparative and Historical Context". KCET. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eagle Rock Historical Society Time Line. Retrieved June 24, 2010

- ^ "Important Dates – Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society". eaglerockhistory.org. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Baker, Bob (September 1, 1985). "A Chronology of the Night Stalker's Spree". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ David Weberman (July 8, 2016). Space and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities Be Places of Tolerance?. Central European University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-963-386-124-0.

Anthony Ocampo (March 2, 2016). The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. Stanford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8047-9754-2.

Loc, Tim (March 16, 2017). "Ten Things You May Not Know About Eagle Rock". LAist. Gothamist LLC. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

Watanabe, Teresa (November 26, 2005). "Artesia Thinks the World of Itself". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 20, 2017.Other times, the actions have brought conflict. A few years ago, a move by Filipino merchants to declare a strip of Eagle Rock Boulevard as Philippine Village sparked an uproar -- and a near fistfight -- among the community's residents

Gorman, Anna (August 22, 2007). "Mall anchors thriving Filipino community". Los Angeles. Retrieved March 20, 2017. - ^ Eastsider, The (June 10, 2015). "Who is responsible for the gentrification of Eagle Rock & Highland Park?". The Eastsider LA. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Kamin, Debra (October 22, 2019). "Highland Park, Los Angeles: A Watchful Eye on Gentrification". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Mapping America," New York Times

- ^ Bariscale, Floyd (August 27, 2007), Big Orange Landmarks: No. 59 - Eagle Rock City Hall, retrieved November 6, 2014

- ^ a b Warren, Eric. Images of America Eagle Rock. Arcadia Publishing 2009

- ^ Andrews, J. C. C. (1984). The Well-Built Elephant. Confusing & Weed. p. 66. ISBN 0-312-92936-6.

- ^ "Eagle Rock Recreation Center". LAParks.org. July 30, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Eagle Rock Dog Park". LAParks.org. August 19, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Eagle Rock Hillside Park". LAParks.org. September 11, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Richard Alatorre Park". LAParks.org. September 2, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ "Yosemite Recreation Center". LAParks.org. August 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Occidental College; A long Tradition. Retrieved on June 24, 2010Archived June 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Occidental College Timeline. Retrieved on June 24, 2010

- ^ "Eagle Rock Jr./Sr. High School". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ "Eagle Rock: Schools". Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ Clelrity Rolas School website

- ^ "Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society". Retrieved on February 23, 2009.

- ^ Deborah Vankin, "Maria Bamford Releases a Comedy Special Direct to Fans," Los Angeles Times, November 12, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society

- ^ "Once official production on The Men began, Brando moved out of the veterans hospital and into a small bungalow owned by his aunt, Betty Lindemeyer, in Eagle Rock, Calif." "Marlon Brando, 1949 | Marlon Brando: Rare Early Photos of the Hollywood Legend in 1949 | LIFE.com". Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013. "Life With Marlon Brando: Early Photos," Life, undated

- ^ "Oh Sees' John Dwyer on What Drives His Endless DIY Quest". Rolling Stone. November 20, 2017.

- ^ Metro Boston News Sunday October 5th Archived September 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Neill, Molly. "M.F.K. Fisher, Writer on the Art of Food and the Taste of Living, Is Dead at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ Frank Parrello, "The Galpins of Eagle Rock" Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society Newsletter (Summer 2012): 3-5.

- ^ "Ryden and Peck," Bizarre, June 2009.

- ^ The Faster Master Plaster Caster

- ^ Los Angeles magazine

- ^ "Tom, William". Los Angeles Times. November 22, 2012. p. AA5. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Lindsay Wagner". Biography. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

Her parents divorced when Wagner was 7 years old, and she moved with her mother to Eagle Rock, a suburb outside Pasadena, California.

- ^ Danny Miller (November 12, 2014). "TCM's 'Starring Virginia Weidler' Honors One of Hollywood's Finest". CinePhiled. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

Barry Monush (2003). Screen World Presents the Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors: From the silent era to 1965. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. p. 777. ISBN 978-1-55783-551-2.