Nikolay Nekrasov

Nikolay Nekrasov | |

|---|---|

Nekrasov in 1870 | |

| Born | Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov 10 December [O.S. 28 November] 1821[1] Nemyriv, Bratslavsky Uyezd, Podolia Governorate, Russian Empire[1] |

| Died | 8 January 1878 [O.S. 27 December 1877] (aged 56)[1] Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire[1] |

| Occupation | Poet, publisher |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Spouse | Fyokla Viktorova |

| Signature | |

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov (Russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, IPA: [nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪtɕ nʲɪˈkrasəf] , 10 December [O.S. 28 November] 1821 – 8 January 1878 [O.S. 27 December 1877]) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publisher, whose deeply compassionate poems about the Russian peasantry made him a hero of liberal and radical circles in the Russian intelligentsia of the mid-nineteenth century, particularly as represented by Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Chernyshevsky. He is credited with introducing into Russian poetry ternary meters and the technique of dramatic monologue (On the Road, 1845).[2] As the editor of several literary journals, notably Sovremennik, Nekrasov was also singularly successful and influential.[3]

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov was born in Nemyriv (now in Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine), in the Bratslavsky Uyezd of Podolia Governorate. His father Alexey Sergeyevich Nekrasov (1788–1862) was a descendant from Russian landed gentry, and an officer in the Imperial Russian Army.[4] There is some uncertainty as to his mother's origins. According to Brokhaus & Efron (and this corresponds with Nekrasov's 1887 autobiographical notes), Alexandra Zakrzewska was a Polish noblewoman, daughter of a wealthy landlord who belonged to szlachta. The church records[clarification needed] tell a different story, and modern Russian scholars have her name as Yelena Andreyevna. "Up until recently the poet's biographers had it that his mother belonged to the Polish family. In fact she was the daughter of Ukrainian state official Alexander Semyonovich Zakrevsky, the owner of Yuzvino, a small village in the Podolia Governorate," Korney Chukovsky asserted in 1967.[5] Pyotr Yakubovich argued that the records[clarification needed] might have been tampered with so as to conceal the fact that the girl had been indeed taken from Poland without her parents' consent (Nekrasov in his autobiography states as much).[6][note 1] D.S.Mirsky came up with another way of explaining this discrepancy by suggesting that Nekrasov "created the cult of his mother, imparted her with improbable qualities and started worshipping her after her death."[7]

In January 1823 Alexey Nekrasov, ranked army major, retired and moved the family to his estate in Greshnevo, Yaroslavl province, near the Volga River, where young Nikolai spent his childhood years with his five siblings, brothers Andrey (b. 1820), Konstantin (b. 1824) and Fyodor (b. 1827), sisters Elizaveta (b. 1821) and Anna (b. 1823).[3][4] This early retirement from the army, as well as his job as a provincial inspector, caused Aleksey Sergeyevich much frustration resulting in drunken rages against both his peasants and his wife. Such experiences traumatized Nikolai and later determined the subject matter of his major poems that portrayed the plight of the Russian peasants and women. Nekrasov's mother loved literature and imparted this passion to her son; it was her love and support that helped the young poet to survive the traumatic experiences of his childhood which were aggravated by images of social injustice, similar to Fyodor Dostoyevsky's childhood recollections.[6][8][9] "His was a wounded heart, and this wound that never healed served as a source for his passionate, suffering verse for the rest of his life," the latter wrote.[4]

Education and literary debut

[edit]

In September 1832 Nekrasov joined the Yaroslavl Gymnasium but quit it prematurely. The reasons for this might have been the alleged trouble with tutors whom he wrote satires on (no archive documents confirm this)[10] as well as Alexey Sergeyevich's insistence that his son should join the military academy. The biographer Vladimir Zhdanov also mentions the father's unwillingness to pay for his children's education; he certainly was engaged at some point in a long-drawn correspondence with the gymnasium authorities on this matter. Finally, in July 1837 he took two of his elder sons back home, citing health problems as a reason, and Nikolai had to spend a year in Greshnevo, doing nothing besides accompanying his father in his expeditions. The quality of education in the gymnasium was poor, but it was there that Nekrasov's interest in poetry grew: he admired Byron and Pushkin, notably the latter's "Ode to Freedom".[3]

According to some sources he was then 'sent' to Saint Petersburg by his father, but Nekrasov in his autobiography maintained that it was his own decision to go, and that his brother Andrey assisted him in trying to persuade their father to procure all the recommendations required.[5] "By the age of fifteen the whole notebook [of verses] has taken shape, which was the reason why I was itching to flee to the capital," he remembered.[8] Outraged by his son's refusal to join the Cadet Corps, the father stopped supporting him financially. The three-year period of his "Petersburg tribulations" followed when the young man had to live in extreme conditions and once even found himself in a homeless shelter.[3] Things turned for the better when he started to give private lessons and contribute to the Literary Supplement to Russky Invalid, all the while compiling ABC-books and versified fairytales for children and vaudevilles, under the pseudonym Perepelsky.[6] In October 1838 Nekrasov debuted as a published poet: his "Thought" (Дума) appeared in Syn Otechestva.[11] In 1839 he took exams at the Saint Petersburg University's Eastern languages faculty, failed and joined the philosophy faculty as a part-time student where he studied, irregularly, until July 1841.[9] Years later detractors accused Nekrasov of mercantilism ("A million was his demon," wrote Dostoyevsky). But, "for eight years (1838–1846) this man lived on the verge of starvation... should he have backstepped, made peace with his father, he'd have found himself again in total comfort," Yakubovish noted. "He might have easily become a brilliant general, outstanding scientist, rich merchant, should he have put his heart to it," argued Nikolai Mikhaylovsky, praising Nekrasov's stubbornness in pursuing his own way.[6]

In February 1840 Nekrasov published his first collection of poetry Dreams and Sounds, using initials "N. N." following the advice of his patron Vasily Zhukovsky who suggested the author might feel ashamed of his childish exercises in several years' time.[11] The book, reviewed favourably by Pyotr Pletnyov and Ksenofont Polevoy, was dismissed by Alexey Galakhov and Vissarion Belinsky. Several months later Nekrasov retrieved and destroyed the unsold bulk of his first collection; some copies that survived have become a rarity since.[9] Dreams and Sounds was indeed a patchy collection, but not such a disaster as it was purported to be and featured, albeit in embryonic state, all the major motifs of the later Nekrasov's poetry.[3][6]

Nekrasov's first literary mentor Fyodor Koni who edited theatre magazines (Repertoire of Russian Theatre, then Pantheon, owned by Nikolai Polevoy), helped him debut as literary critic. Soon he became a prolific author and started to produce satires ("The Talker", "The States Official") and vaudevilles ("The Actor", "The Petersburg Money-lender"), for this publication and Literaturnaya Gazeta. Nekrasov's fondness for theater prevailed through the years, and his best poems (Russian Women, The Railway, The Contemporaries, Who Is Happy in Russia?) all had a distinct element of drama to them.[4]

In October 1841 Nekrasov started contributing to Andrey Krayevsky's Otechestvennye Zapiski (which he did until 1846), writing anonymously.[11] The barrage of prose he published in the early 1840s was, admittedly, worthless, but several of his plays (notably, No Hiding a Needle in a Sack) were produced at the Alexandrinsky Theatre to some commercial success.[4] In 1842 (a year after his mother's death) Nekrasov returned to Greshnevo and made peace with his father who was now quite proud of his son's achievements.[6]

In 1843 Nekrasov met Vissarion Belinsky and entered his circle of friends which included Ivan Turgenev, Ivan Panayev and Pavel Annenkov. Belinsky, obsessed with the ideas of the French Socialists, found a great sympathizer in Nekrasov for whom horrors of serfdom in his father's estate were still a fresh memory.[4] "On the Road" (1845) and "Motherland" (1846), two of Nekrasov's early realistic poems, delighted Belinsky.[12] The poet claimed later that those early conversations with Belinsky changed his life and commemorated the critic in several poems ("In the Memory of Belinsky", 1853; "V.G.Belinsky", 1855; "Scenes from The Bear Hunt", 1867). Before his death in 1848, Belinsky granted Nekrasov rights to publish various articles and other material originally planned for an almanac, to be called the "Leviathan".[4]

In the mid-1840s Nekrasov compiled, edited and published two influential almanacs, The Physiology of Saint Petersburg (1845)[note 2] and Saint Petersburg Collection (1846), the latter featuring Fyodor Dostoyevsky's first novel, Poor Folk. Gathering the works of several up and coming authors (Ivan Turgenev, Dmitry Grigorovich, Vladimir Dal, Ivan Panayev, Alexander Hertzen, Fyodor Dostoyevsky among them), both books were instrumental in promoting the new wave of realism in Russian literature. Several Nekrasov's poems found their way into the First of April compilation of humour he published in April 1846. Among the curiosities featured there was the novel The Danger of Enjoying Vain Dreams, co-authored by Nekrasov, Grigorovich and Dostoyevsky.[11] Among the work of fiction written by Nekrasov in those years was his unfinished autobiographical novel The Life and Adventures of Tikhon Trostnikov (1843–1848); some of its motifs would be found later in his poetry ("The Unhappy Ones", 1856; On the Street, 1850, "The Cabman", 1855). Part of it, the "St. Petersburg Corners", featured in the Physiology of St. Petersburg, was treated later as an independent novelette, an exponent of the "natural school" genre.[4][13]

Sovremennik and Otechestvennye Zapiski

[edit]

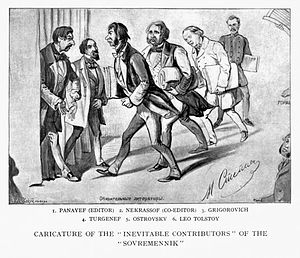

In November 1846 Panayev and Nekrasov acquired[note 3] a popular magazine Sovremennik which had been founded by Alexander Pushkin but lost momentum under Pyotr Pletnyov. Much of the staff of the old Otechestvennye Zapiski, including Belinsky, abandoned Andrey Krayevsky's magazine, and joined Sovremennik to work with Nekrasov, Panayev and Alexander Nikitenko, a nominal editor-in-chief. In the course of just several months Nekrasov managed to draw to the invigorated magazine the best literary forces of Russia. Among the works published in it in the course of the next several years were Ivan Turgenev's A Sportsman's Sketches, Dmitry Grigorovich's Anton Goremyka, Ivan Goncharov's A Common Story, Alexander Hertzen’s Magpie the Thief and Doctor Krupov. One of the young authors discovered by Nekrasov was Leo Tolstoy who debuted in Sovremennik with his trilogy Childhood, Boyhood and Youth.[4]

Nekrasov managed to save the magazine during the 'Seven years of darkness' period (1848–1855) when it was balancing on the verge of closure and he himself was under the secret police' surveillance.[11] In order to fill up the gaps caused by censorial interference he started to produce lengthy picturesque novels (Three Countries of the World, 1848–1849, The Dead Lake, 1851), co-authored by Avdotya Panayeva, his common-law wife.[4][14] His way of befriending censors by inviting them to his weekly literary dinners proved to be another useful ploy. Gambling (a habit shared by male ancestors on his father's side; his grandfather lost most of the family estate through it) was put to the service too, and as a member of the English Club Nekrasov made a lot of useful acquaintances.[4]

In 1854 Nekrasov invited Nikolai Chernyshevsky to join Sovremennik, in 1858 Nikolai Dobrolyubov became one of its major contributors. This led to the inevitable radicalisation of the magazine and the rift with its liberal flank. In 1859 Dobrolyubov's negative review outraged Turgenev and led to his departure from Sovremennik.[11] But the influx of young radical authors continued: Nikolai Uspensky, Fyodor Reshetnikov, Nikolai Pomyalovsky, Vasily Sleptsov, Pyotr Yakubovich, Pavel Yakushkin, Gleb Uspensky soon entered the Russian literary scene.[4] In 1858 Nekrasov and Dobrolyubov founded Svistok (Whistle), a satirical supplement to Sovremennik. The first two issues (in 1859) were compiled by Dobrolyubov, from the third (October 1858) onwards Nekrasov became this publication's editor and regular contributor.[15]

In June 1862, after the series of arsons in Petersburg for which radical students were blamed, Sovremennik was closed, and a month later Chernyshevsky was arrested. In December Nekrasov managed to get Sovremennik re-opened, and in 1863 published What Is to Be Done? by the incarcerated author.[4]

In 1855 Nekrasov started working upon his first poetry collection and on 15 October 1856, The Poems by N. Nekrasov came out to great public and critical acclaim.[4] "The rapture is universal. Hardly Pushkin's first poems, or Revizor, or Dead Souls could be said to have enjoyed such success as your book," wrote Chernyshevsky on 5 November to Nekrasov who was abroad at the time, receiving medical treatment.[16] "Nekrasov's poems… brandish like fire," wrote Turgenev.[17] "Nekrasov is an idol of our times, a worshipped poet, he is now bigger than Pushkin," wrote memoirist Elena Stakensneider.[4][11] Upon his return in August 1857, Nekrasov moved into the new flat in the Krayevsky's house on Liteiny Lane in Saint Petersburg where he resided since then for the rest of his life.[11]

The 1861 Manifest left Nekrasov unimpressed. "Is that freedom? More like a fake, a jibe at peasants," he said, reportedly, to Chernyshevsky on 5 March, the day of the Manifest's publication. His first poetic responses to the reform were "Freedom" ("I know, instead of the old nets they'd invented some new ones...")[18] and Korobeiniki (1861). The latter was originally published in the Red Books series started by Nekrasov specifically for the peasant readership. These books were distributed by 'ophens', vagrant traders, not unlike the korobeinikis Tikhonych and Ivan, the two heroes of the poem.[4] After the second issue the series were banned by censors.[11]

In 1861 Nekrasov started campaigning for the release of his arrested colleague, Mikhail Mikhaylov, but failed: the latter was deported to Siberia. More successful was his plea for the release of Afanasy Shchapov: the decree ordering the Petersburg historian's demotion to a monastery was retrieved by Alexander II.[11] After his father's death, Nekrasov in May 1862 bought the Karabikha estate, visiting it on a yearly basis until his own death.[4]

In April 1866, after Dmitry Karakozov's attempt on the life of the Tsar, Nekrasov, so as to save Sovremennik from closure,[11] wrote the "Ode to Osip Komissarov" (the man who saved the monarch's life by pushing Karakozov aside) to read it publicly in the English Club. His another poetic address greeted Muravyov the Hangman, a man responsible for the brutal suppression of the 1863 Polish Uprising, who was now in charge of the Karakozov case. Both gestures proved to be futile and in May 1866 Sovremennik was closed for good.[11]

In the end of 1866 Nekrasov purchased Otechestvennye Zapiski to become this publication's editor with Grigory Yeliseyev as his deputy (soon joined by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin) and previous owner Krayevsky as an administrator.[11] Among the authors attracted to the new OZ were Alexander Ostrovsky and Gleb Uspensky. Dmitry Pisarev, put in charge of the literary criticism section, was later succeeded by Alexander Skabichevsky and Nikolai Mikhaylovsky.[4]

In 1869 OZ started publishing what turned out to be Nekrasov's most famous poem, Who Is Happy in Russia? (1863–1876). In 1873 a group of narodniks in Geneva printed the misleadingly titled, unauthorized Collection of New Poems and Songs by Nekrasov, featuring all the protest poems banned in Russia, a clear sign of what an inspiration now the poet has become for the revolutionary underground.[11]

Illness and death

[edit]

For many years Nikolai Nekrasov suffered from a chronic throat condition.[9] In April 1876 severe pains brought about insomnia that lasted for months. In June Saltykov-Shchedrin arrived from abroad to succeed him as an editor-in-chief of OZ. Still unsure as to the nature of the illness, doctor Sergey Botkin advised Nekrasov to go to the Crimea. In September 1876 he arrived at Yalta where he continued working on Who Is Happy in Russia's final part, "The Feast for All the World". Banned by censors, it soon started spreading in hand-written copies all over Russia.[11] Already in 1875 the high-profile concilium led by Nikolay Sklifosovsky had diagnosed the intestinal cancer.[19]

In February 1877 groups of radical students started to arrive to Yalta from all over the country to provide moral support for the dying man. Painter Ivan Kramskoy came to stay and work upon the poet's portrait. One of the last people Nekrasov met was Ivan Turgenev who came to make peace after years of bitter feud.[11] The surgery performed on 12 April 1877 by Theodor Billroth who was invited from Vienna by Anna Alexeyevna Nekrasova brought some relief, but not for long.[11] "I saw him for the last time just one month before his death. He looked like a corpse... Not only did he speak well, but retained the clarity of mind, seemingly refusing to believe the end was near," remembered Dostoyevsky.[20]

Nikolai Alekseyevich Nekrasov died on 8 January 1878. Four thousand people came to the funeral and the procession leading to the Novodevichy Cemetery turned into a political rally.[11] Fyodor Dostoyevsky delivered a keynote eulogy, calling Nekrasov the greatest Russian poet since Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov. One section of the crowd, the followers of Chernyshevsky (with Georgy Plekhanov as one of their leaders), chanted "No, he was greater!"[21] Members of Zemlya i Volya, alongside other radical groups (with wreaths "From the Socialists"), were also present. "His funeral was one of the most striking demonstrations of popularity ever accorded to a Russian writer," according to Mirsky.[22]

Private life

[edit]

Nikolai Nekrasov met the already married Avdotya Panayeva in 1842 when she was already a promising writer and a popular hostess of a literary salon. The 20-year-old Nekrasov fell in love but had to wait several years for her emotional response and at least on one occasion was on the verge of suicide, if one of his Panayeva Cycle poems, "Some time ago, rejected by you... " is to be believed. For several years she was "struggling with her feelings" (according to Chernyshevsky), then in 1847 succumbed. "This was the lucky day I count as my whole life's beginning," wrote Nekrasov later.[3]

The way Nekrasov moved into Panayev's house to complete a much-ridiculed love triangle seen by many as a take on the French-imported idea of the 'unfettered love' which young Russian radicals associated with the Socialist moral values. In reality the picture was more complicated. Ivan Panayev, a gifted writer and journalist, proved to be 'a family man of bachelor habits', and by the time of Nekrasov's arrival their marriage has been in tatters. Avdotya who saw gender inequality as grave social injustice, considered herself free from marital obligations but was still unwilling to sever ties with a good friend. A bizarre romantic/professional team which united colleagues and lovers (she continued 'dating' her husband, sending her jealous lodger into fits of fury) was difficult for both men, doubly so for a woman in a society foreign to such experiments.[3]

The Panayevs' home soon became the unofficial Sovremennik' headquarters. In tandem with Panayeva (who used the pseudonym N. N. Stanitsky) Nekrasov wrote two huge novels, Three Countries of the World (1848–1849) and The Dead Lake (1851). Dismissed by many critics as little more than a ploy serving to fill the gaps in Sovremennik left by censorial cuts and criticised by some of the colleagues (Vasily Botkin regarded such a manufacture as 'humiliating for literature'), in retrospect they are seen as uneven but curious literary experiments not without their artistic merits.[3]

Nekrasov's poems dedicated to and inspired by Avdotya formed the Panayeva Cycle which amounted "in its entirety... to a long poem telling the passionate, often painful and morbid love story," according to a biographer.[23][24] It is only these poems that the nature of their tempestuous relationship could be judged by. There was a correspondence between them, but in a fit of rage Panayeva destroyed all letters ("Now, cry! Cry bitterly, you won’t be able to re-write them," – Nekrasov reproached her in a poem called "The Letters"). Several verses of this cycle became musical romances, one of them, "Forgive! Forget the days of the fall..." (Прости! Не помни дней паденья...) has been set to music by no less than forty Russian composers, starting with Cesar Cui in 1859, and including Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky.[25]

In 1849 Panayeva gave birth to a son, but the boy soon died. Another death, of Ivan Panayev in 1862, drove the couple still further apart.[26] The main reason for Panayeva's final departure, though, was Nekrasov's 'difficult' character. He was prone to fits of depression, anger, hypochondria and could spend days "sprawling on a couch in his cabinet, greatly irritated, telling people how he hated everybody but mostly himself," according to Zhdanov.[3] "Your laughter, your merry talking could not dispel my morbid thoughts/They only served to drive my heavy, sick and irritated mind insane," he confessed in a poem.[27]

In 1863, while still with Panayeva, Nekrasov met the French actress Celine Lefresne, who was at the time performing at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre with her troupe. She became his lover; Nekrasov, when in France, stayed in her Paris flat several times; she made a visit to Karabikha in 1867. Celine was a kindred spirit and made his journeys abroad a joy, although her attitude towards him has been described as 'dry'. Nekrasov helped Celine financially and bequeathed her a considerable sum of money (10,5 thousand rubles).[28]

In 1870 Nekrasov met and fell in love with 19-year-old Fyokla Anisimovna Viktorova, a country girl for whom he invented another name, Zinaida Nikolayevna (the original one was deemed too 'simple').[3] Educated personally by her lover, she soon learned many of his poems by heart and became in effect his literary secretary. Zina was treated respectfully by the poet's literary friends, but not by Anna Alexeyevna, Nekrasov's sister who found such mésalliance unacceptable. The two women made peace in the mid-1870s, as they were bedsitting in turns for the dying poet. On 7 April 1877, in a symbolic gesture of gratitude and respect, Nekrasov wed Zinaida Nikolayevna at his home.[29]

Works

[edit]Nekrasov's first collection of poetry, Dreams and Sounds (Мечты и звуки), received some favourable reviews but was dismissed as 'bland and mediocre'[6] by Vissarion Belinsky. It was Belinsky, though, who first recognized in Nekrasov the talent of a harsh and witty realist. "Do you know that you are indeed a poet, and the true one?" he exclaimed upon reading the poem, "On the Road" (В дороге, 1845), as Ivan Panayev recalled. According to Panayev, the autobiographical "Motherland" (Родина, 1846), banned by censors and published ten years later, "drove Belinsky totally crazy, he learnt it by heart and sent it to his Moscow friends".[12][30]

"When from the darkness of delusion..." (Когда из мрака заблужденья..., 1845), arguably the first poem in Russia about the plight of a woman driven to prostitution by poverty, brought Chernyshevsky to tears. Of "Whether I ride the dark street though the night..." (Еду ли ночью по улице темной..., 1847), another harrowing story of a broken family, dead baby and a wife having to sell her body to procure money for a tiny coffin, Ivan Turgenev wrote in a letter to Belinsky (14 November): "Please tell Nekrasov that... [it] drove me totally mad, I repeat it day and night and have learnt it by heart."[31] According to literary historian D.S. Mirsky, the early verse beginning 'Whether I ride the dark street through the night...', is "truly timeless... recognized by many (including Grigoryev and Rozanov) as something so much more important than just a verse – the tragic tale of a doomed love balancing on the verge of starvation and moral fall".[7]

The Poems by N. Nekrasov, published in October 1856, made their author famous. Divided into four parts and opening with the manifest-like "The Poet and the Citizen" (Поэт и гражданин), it was organized into an elaborate tapestry, parts of it interweaved to form vast poetic narratives (like On the Street cycle). Part one was dealing with the real people's life, part two satirised 'the enemies of the people', part three revealed the 'friends of the people, real and false', and part four was a collection of lyric verses on love and friendship. The Part 3's centerpiece was Sasha (Саша, 1855), an ode to the new generation of politically minded Russians, which critics see as closely linked to Turgenev's Rudin.[4] In 1861 the second edition of The Poems came out (now in 2 volumes). In Nekrasov's lifetime this ever-growing collection has been re-issued several times.[4] The academic version of the Complete N.A. Nekrasov, ready by the late 1930s, had to be shelved due to the break out of the World War II; it was published in 12 volumes by the Soviet Goslitizdat in 1948–1953.[32]

1855–1862 were the years of Nekrasov's greatest literary activity.[33] One important poem, "Musings By the Front Door" (Размышления у парадного подъезда, 1858), was banned in Russia and appeared in Hertzen's Kolokol in January 1860.[11] Among others were "The Unhappy Ones" (Несчастные, 1856), "Silence" (Тишина, 1857) and "The Song for Yeryomushka" (Песня Еремушке, 1859), the latter turned into a revolutionary hymn by the radical youth.[4]

Nekrasov responded to the 1861 land reform with Korobeiniki (Коробейники, 1861), the tragicomic story of the two 'basket-men', Tikhonych and Ivan, who travel across Russia selling goods and gathering news. The fragment of the poem's first part evolved into a popular folk song.[4] "The most melodious of Nekrasov's poems is Korobeiniki, the story which, although tragic, is told in the life-affirming, optimistic tone, and yet features another, strong and powerful even if bizarre motif, that of 'The Wanderer's Song'," wrote Mirsky.[7]

Among Nekrasov's best known poems of the early 1860 were "Peasant Children" (Крестьянские дети, 1861), highlighting moral values of the Russian peasantry, and "A Knight for an Hour" (Рыцарь на час, 1862), written after the author's visit to his mother's grave.[34] "Orina, the Soldier's Mother" (Орина, мать солдатская, 1863) glorified the motherly love that defies death itself, while The Railway (Железная дорога, 1964), condemning the Russian capitalism "built upon peasant's bones," continued the line of protest hymns started in the mid-1840s.[4]

"Grandfather Frost the Red Nose" (Мороз, Красный нос, 1864), a paean to the Russian national character, went rather against the grain with the general mood of the Russian intelligentsia of the time, steeped in soul-searching after the brutal suppression of the Polish Uprising of 1863 by the Imperial forces.[4] "Life, this enigma you've been thrown into, each day draws you nearer to demolition, frightens you and seems maddeningly unfair. But then you notice that somebody needs you, and all of a sudden your whole existence gets filled with the meaning; the feeling that you're an orphan needed by nobody, is gone", wrote Nekrasov to Lev Tolstoy, explaining this poem's idea.[35]

In the late 1860s Nekrasov published several important satires. The Contemporaries (Современники, 1865), a swipe at the rising Russian capitalism and its immoral promoters,[4] is considered by Vladimir Zhdanov as being on par with the best of Saltykov-Shchedrin's work. The latter too praised the poem for its power and realism.[36] In 1865 the law was passed abolishing preliminary censorship but toughening punitive sanctions. Nekrasov lambasted this move in his satirical cycle Songs of the Free Word (Песни свободного слова), the publication of which caused more trouble for Sovremennik.[11]

Illustration by Boris Kustodiev

In 1867 Nekrasov started his Poems for Russian Children cycle, concluded in 1873. Full of humour and great sympathy for the peasant youth, "Grandfather Mazay and the Hares" (Дедушка Мазай и зайцы) and "General Stomping-Bear" (Генерал Топтыгин) up to this day remain the children's favourites in his country.[4]

The rise of the Narodniks in the early 1870s coincided with the renewal of interest in the Decembrist revolt in Russia. It was reflected in first Grandfather (Дедушка, 1870), then in a dilogy called Russian Women ("Princess Trubetskaya", 1872; "Princess M.N. Volkonskaya, 1873), the latter based upon the real life stories of Ekaterina Trubetskaya and Maria Volkonskaya, who followed their Decembrist husbands to their exile in Siberia.[4][11]

In the 1870s the general tone of Nekrasov's poetry changed: it became more declarative, over-dramatized and featured the recurring image of poet as a priest, serving "the throne of truth, love and beauty." Nekrasov's later poetry is the traditionalist one, quoting and praising giants of the past, like Pushkin and Schiller, trading political satire and personal drama for elegiac musings.[37] In poems like "The Morning" (Утро, 1873) and "The Frightful Year" (Страшный год, 1874) Nekrasov sounds like a precursor to Alexander Blok, according to biographer Yuri Lebedev. The need to rise above the mundane in search for universal truths forms the leitmotif of the lyric cycle Last Songs (Последние песни, 1877).[4]

Among Nekrasov's most important works is his last, unfinished epic Who Is Happy in Russia? (Кому на Руси жить хорошо?, 1863–1876), telling the story of seven peasants who set out to ask various elements of the rural population if they are happy, to which the answer is never satisfactory. The poem, noted for its rhyme scheme ("several unrhymed iambic tetrameters ending in a Pyrrhic are succeeded by a clausule in iambic trimeter"[38]) resembling a traditional Russian folk song, is regarded Nekrasov's masterpiece.[4][9]

Recognition and legacy

[edit]

Nikolai Nekrasov is considered one of the greatest Russian poets of the 19th century, alongside Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov.[4] In the 1850s and 1860s, Nekrasov (backed by two of his younger friends and allies, Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov) became the leader of a politicized, social justice-oriented trend in Russian poetry (evolved from the Gogol-founded natural school in prose) and exerted a strong influence upon the young radical intelligentsia. "What prompted the Russian student's inclination to 'merge with the people' was not Western Socialism, but the Narodnik-related poetry of Nekrasov, which was immensely popular among the young people," argued the revolutionary poet Nikolai Morozov.[39]

Nekrasov, as a real innovator in Russian literature, was closely linked to the tradition set by his great predecessors, first and foremost, Pushkin. – Korney Chukovsky, 1952[40]

Nekrasov was totally devoid of memory, unaware of any tradition and foreign to the notion of historical gratitude. He came from nowhere and drew his own line, starting with himself, never much caring for anybody else. – Vasily Rozanov, 1916[41]

In 1860 the so-called 'Nekrasov school' in Russian poetry started to take shape, uniting realist poets like Dmitry Minayev, Nikolai Dobrolyubov, Ivan Nikitin and Vasily Kurochkin, among others. Chernyshevsky praised Nekrasov for having started "a new period in the history of Russian poetry."[4]

Nekrasov was credited with being the first editor of Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose debut novel Poor Folk made its way into the St. Petersburg Collection which, along with its predecessor, 1845's The Physiology of Saint Petersburg, played a crucial role in promoting realism in Russian literature. A long-standing editor and publisher of Sovremennik, Nekrasov turned it into the leading Russian literary publication of its time, thus continuing the legacy of Pushkin, its originator. During its 20 years of steady and careful literary policy, Sovremennik served as a cultural forum for all the major Russian writers, including Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev, and Leo Tolstoy, as well as Nekrasov's own poetry and prose. His years at the helm of Sovremennik, though, were marred by controversy. According to Mirsky, "Nekrasov was a genius editor, and his gift for procuring the best literature and the best authors at the height of their relevancy, bordered on miraculous," but he was also "first and foremost, a ruthless manipulator, for whom any means justified the end" and he "shamelessly exploited the enthusiasm of his underpaid authors."[7]

The conservatives among his contemporaries regarded him a dangerous political provocateur. "Nekrasov is an outright communist... He's openly crying out for the revolution," reported Faddey Bulgarin in his letter to the Russian secret police chief in 1846.[42] Liberal detractors (Vasily Botkin, Alexander Druzhinin, Ivan Turgenev among them) were horrified by the way "ugly, anti-social things creep into his verse," as Boris Almazov has put it,[43] and the 'antipoetic' style of his verse (Grigoryev, Rozanov).[44] "The way he pushes such prosaic subject matter down into poetic form, is just unthinkable," Almazov wrote in 1852.[45] "Nekrasov most definitely is not an artist," insisted Stepan Dudyshkin in 1861.[46]

Attacks from the right and the center-right caused Nekrasov's reputation no harm and "only strengthened [his] position as a spiritual leader of the radical youth," as Korney Chukovsky maintained. More damage has been done (according to the same author) by those of his radical followers who, while eulogizing 'Nekrasov the tribune,' failed to appreciate his 'genius of an innovator'.[47] "His talent was remarkable if not for its greatness, then for the fine way it reflected the state of Russia of his time," wrote soon after Nekrasov's death one of his colleagues and allies Grigory Yeliseyev.[48] "Nekrasov was for the most part a didactic poet and as such... prone to stiltedness, mannerisms and occasional insincerity," opined Maxim Antonovich.[49] Georgy Plekhanov who in his 1902 article glorified 'Nekrasov the Revolutionary' insisted that "one is obliged to read him... in spite of occasional faults of the form" and his "inadequacy in terms of the demands of esthetic taste."[50]

According to one school of thought (formulated among others by Vasily Rosanov in his 1916 essay), Nekrasov in the context of the Russian history of literature was an "alien... who came from nowhere" and grew into a destructive 'anti-Pushkin' force to crash with his powerful, yet artless verse the tradition of "shining harmonies" set by the classic.[41] Decades earlier Afanasy Fet described Nekrasov's verse as a 'tin-plate prose' next to Pushkin's 'golden poetry'. Korney Chukovsky passionately opposed such views and devoted the whole book, Nekrasov the Master, to highlight the poet's stylistic innovations and trace the "ideological genealogy", as he put it, from Pushkin through Gogol and Belinsky to Nekrasov.[33][51] Mirsky, while giving credit to Chukovsky's effort, still saw Nekrasov as a great innovator who came first to destroy, only then to create: "He was essentially a rebel against all the stock in trade of 'poetic poetry' and the essence of his best work is precisely the bold creation of a new poetry unfettered by traditional standards of taste," Mirsky wrote in 1925.[7]

Modern Russian scholars consider Nekrasov a trailblazer in the Russian 19th-century poetry who "explored new ways of its development in such a daring way that before him was plain unthinkable," according to biographer Yuri Lebedev. Mixing social awareness and political rhetoric with such conservative subgenres as elegy, traditional romance and romantic ballad, he opened new ways, particularly for the Russian Modernists some of whom (Zinaida Gippius, Valery Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Alexander Blok) professed admiration for the poet, citing him as an influence.[4] Vladimir Mayakovsky did as much in the early 1920s, suggesting that Nekrasov, as 'a brilliant jack-of-all-trades' would have fitted perfectly into the new Soviet poetry scene.[52]

Nekrasov enriched the traditional palette of the Russian poetry language by adding to it elements of satire, feuilleton, realistic sketch and, most importantly, folklore and song-like structures. "Of all the 19th century poets he was the only one so close to the spirit of a Russian folk song, which he never imitated – his soul was that of a folk singer," argued Mirsky. "What distinguishes his verse is its song-like quality," wrote Zinaida Gippius in 1939.[53] "The greatest achievement in the genre of the folk Russian song," according to Misky is the poem Who Is Happy in Russia?, its style "totally original, very characteristic and monolith. Never does the poet indulge himself with his usual moaning and conducts the narrative in the tone of sharp but good-natured satire very much in the vein of a common peasant talk... Full of extraordinary verbal expressiveness, energy and many discoveries, it's one of the most original Russian poems of the 19th century."[7]

Nekrasov is recognized as an innovator satirist. Before him the social satire in Russia was "didactic and punishing": the poet satirist was supposed to "rise high above his targets to bombard them easily with the barrage of scorching words" (Lebedev). Nekrasov's dramatic method implied the narrator's total closeness to his hero whom he 'played out' as an actor, revealing motives, employing sarcasm rather than wrath, either ironically eulogizing villains ("Musings by the Front Door"), or providing the objects of his satires a tribune for long, self-exposing monologues ("A Moral Man", "Fragments of the Travel Sketches by Count Garansky", "The Railroad").[4]

What interested Nekrasov himself so much more than the stylistic experiments, though, was the question of "whether poetry could change the world" and in a way he provided an answer, having become by far the most politically influential figure in the Russian 19th-century literature. Vladimir Lenin considered him "the great Russian Socialist"[54] and habitually treated his legacy as a quotation book which he used to flay enemies, left and right.[40] In the Soviet times scholars tended to promote the same idea, glorifying Nekrasov as a 'social democrat poet' who was 'fighting for the oppressed' and 'hated the rich'.[55]

Unlike many of his radical allies, though, Nekrasov held the Orthodox Christianity and 'traditional Russian national values' in high esteem. "He had an unusual power of idealization and the need to create gods was the most profound of his needs. The Russian people was the principal of these gods; next to it stood equally idealized and subjectively conditioned myths of his mother and Belinsky," noted Mirsky. Nekrasov's poetry was admired and profusely quoted by liberals, monarchists, and nationalists, as well as Socialists.[55] Several of his lines (like "Seyat razumnoye, dobroye, vetchnoye..." – "To saw the seeds of all things sensible, kind, eternal..." or "Suzhdeny vam blagiye poryvi/ No svershit nichevo ne dano". – "You're endowed with the best of intentions / Yet unable to change anything") became the commonplace aphorisms in Russia, overused in all kinds of polemics.[56]

With verdicts upon Nekrasov's legacy invariably depending upon the political views of reviewers, the objective evaluation of Nekrasov's poetry became difficult. As D.S. Mirsky noted in 1925, "Despite his enormous popularity among the radicals and of a tribute given to him as a poet by enemies like Grigoryiev and Dostoyevsky, Nekrasov can hardly be said to have had his due during his lifetime. Even his admirers admired the matter of his poetry rather than its manner, and many of them believed that Nekrasov was a great poet only because matter mattered more than form and in spite of his having written inartistically. After Nekrasov's death his poetry continued to be judged along the party lines, rejected en bloc by the right wing and praised in spite of its inadequate form by the left. Only in relatively recent times has he come into his own, and his great originality and newness being fully appreciated."[7]

Memory

[edit]The centenary of his birth in 1921 was marked by the publication of N.A.Nekrasov: On the Centenary of his Birth by Pavel Lebedev-Polianskii. Nekrasov's estate in Karabikha, his St. Petersburg home, as well as the office of Sovremennik magazine on Liteyny Prospekt, are now national cultural landmarks and public museums of Russian literature. Many Libraries are named in his honor. One of them is the Central Universal Science Nekrasov Library in Moscow. Ukrainian composer Tamara Maliukova Sidorenko (1919–2005) set some of his poems to music.[57]

Selected bibliography

[edit]Poetry

[edit]

|

Plays[edit]

Fiction[edit]

|

|

Notes

[edit]- ^ Yakubovich dismissed the once popular notion of a Polish girl having been kidnapped by a visiting Russian officer against her will, pointing to "Mother", Nekrasov's autobiographical verse describing an episode when he discovered in his family archives his mother's letter written hectically (and apparently in a fit of passion, in French and Polish) which suggested she was at least for a while deeply in love with the army captain.

- ^ The term "physiology" was applied in those times to a short literary real life sketch, describing in detail the life of a certain social strata, group of professionals, etc.

- ^ Panayev donated 35 thousand rubles. The Kazan Governorate landlord Grigory Tolstoy was not among the sponsors, contrary to what some Russian sources maintain. Tolstoy, who ingratiated himself with the mid-19th-century Russian revolutionary circles in France (and was even mentioned in the Marx-Engels correspondence, as a 'fiery Russian revolutionary' who, after having had the long conversation with Marx, declared his intention to sell his whole estate and give the moneys to the revolutionary cause, but seemed to forget about the promise upon his return home) indeed promised Nekrasov to provide the necessary sum, but failed to produce a single kopeck, according to Korney Chukovsky's essay Nekrasov and Grigory Tolstoy.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Nikolay Alekseyevich Nekrasov. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Cizevskij, Dmitrij (1974). History of Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0826511880

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhdanov, Vladimir (1971). "Nekrasov". Molodaya Gvardiya Publishers. ЖЗЛ (The Lives of Distinguished People) series. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Lebedev, Yu. V. (1990). "Nekrasov, Nikolai Alekseyevich". Russian Writers. Biobibliographical Dictionary. Vol. 2. Ed. P.A.Nikolayev. Moscow. Prosveshchenye Publishers. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b Chukovsky, K.I. (1967) Commentaries to N.A.Nekrasov's Autobiography. The Works by N.A.Nekrasov in 8 vols. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow. Vol. VIII. pp. 463–475.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yakubovich, Pyotr (1907). "Nikolai Nekrasov. His Life and Works". Florenty Pavlenkov’s Library of Biographies. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mirsky, D.S. (1926). "Nekrasov, N.A. The History of Russian Literature from Ancient Times to 1925. (Russian translation by R.Zernova)". London: Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd, 1992. Pp. 362–370. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b Nekrasov N.A. Materials for Biography. 1872. The Works by N.A.Nekrasov in 8 vol. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow. 1967. Vol. VIII. Pp. 413–416.

- ^ a b c d e "Nekrasov, Nikolai Alexeyevich". Russian Biographical Dictionary. 1911.

- ^ The Works by A. Skabichevsky, Vol. II, Saint Petersburg, 1895, p.245

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Garkavi, A.M. N.A.Nekrasov's biography. Timeline. The Works by N.A.Nekrasov in 8 vol. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow. 1967. Vol. VIII. Pp. 430–475

- ^ a b Panayev, Ivan. Literary Memoirs. Leningrad, 1950. P.249.

- ^ Zhdanov, p. 335.

- ^ An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers, Volume 1, Taylor & Francis, 1991.

- ^ Maksimovich, A.Y. Nekrasov in The Whistle. Literary Heritage. The USSR Academy of Science. 1946. Vol. 49/50. Book I. Pp. 298—348

- ^ The Complete N.Chernyshevsky, Vol. XIV. P. 321.

- ^ The Complete Works by I.Turgenev in 28 volumes. Letters. Vol. III. P. 58.

- ^ Zhdanov, p.364

- ^ Zeytlin, A. G. (1934). Nekrasov Nikolay Alekseevich. Literary Encyclopedia. Tome 7. (Ed.) Lunacharsky, A. V. (in Russian). Moscow: OGIZ RSFSR, Encyclopedia of the Soviet Union. pp. 678–706. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Dostoyevsky, F.M. (2006) The Diary of a Writer. Russian Classics. Moscow. p. 601

- ^ Dostoyevsky, F.M. (2006) The Diary of a Writer. Russian Classics. Moscow. p. 604

- ^ Mirsky, D.S. (1926). Nekrasov, N.A. The History of Russian Literature from Ancient Times to 1925. (curtailed version) London: Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd. pp. 362–370. ISBN 9780810116795.

- ^ Yevgenyev-Maximov, V. The Life and Works of N. A. Nekrasov, Vol. 2. 1950, р. 272.

- ^ Kuzmenko, Pavel. The Most Scandalous Triangles of the Russian History. Moscow, Astrel Publishers2012

- ^ Ivanov, G.K. (1966) Russian Poetry in Music. Moscow. pp. 245–246.

- ^ Chukovsky, Korney. N. A. Nekrasov and A. Y. Panayeva. 1926

- ^ Ni smekh, no govor tvoi vesyoly / Ne progonyali tyomnykh dum: / Oni besili moi tyazholy, / Bolnoi i razdrazhonny um.

- ^ Stepina, Maria. Nekrasov and Celine Lefresne-Potcher[permanent dead link]. Commentaries to one episode of the biography. Nekrasov Almanac. Nauka Publishers, Saint Petersburg, Vol XIV. Pp 175—177

- ^ Skatov, Nikolai. Fyokla Anisimovna Viktorova, alias Zinaida Nikolayevna Nekrasova. Molodaya Gvardiya. The Lives of Distinguished People series. 1994. ISBN 5-235-02217-3

- ^ Chukovsky, K.I., Garkavi, A.M. (1967) The Works by N.A.Nekrasov in 8 vol. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow. Commentaries. Vol. I. pp. 365–415

- ^ Turgenev, Ivan. Letters in 13 volumes. Vol.I, Moscow-Leningrad, 1961, p. 264.

- ^ Notes to the Works by N.A.Nekrasov in 8 vol. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow. 1967. Vol. I. P. 365.

- ^ a b Korney Chukovsky. Teachers and Precursors. Gogol. IV. 77–141

- ^ Kovalevsky, P.M. Poems and Memoirs. Petrograd, 1912. P. 279.

- ^ The Complete N.A. Nekrasov. Moscow, 1952. Vol. X. pp. 344–345.

- ^ Zhdanov, 376.

- ^ Skatov, N.N. Nekrasov. Contemporaries and Followers// Современники и продолжатели. P.258

- ^ Terras, Victor. A History of Russian Literature. p. 319. ISBN 0-300-04971-4

- ^ Morozov, N.A. Stories of My Life // Повести моей жизни. Moscow, 1955.Vol I. P. 352).

- ^ a b Chukovsky, Vol.V, p.470

- ^ a b Rozanov, Vasily. Novoye Vremya, 1916, No.4308. 8 January

- ^ Shchyogolev, Pavel. One Episode in the Life of V.G. Belinsky. Days of the Past. 1906. No.10, p. 283

- ^ Boris Almazov, Moskvityanin, No.17. Section VII. P.19

- ^ Apollon Grigoryev. Moskvityanin. 1855, Nos. 15–16, p.178

- ^ Moskvityanin, 1852. No.13. Section V, p. 30.

- ^ Otechestvennye Zapiski, 1861, No.12, pp. 87, 194

- ^ Chukovsky, Korney (1966) Nekrasov the Master. The Works by Korney Chukovsky. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow. Vol. 4, pp. 186–187

- ^ Otechestvennye Zapiski. 1878. No.3, p. 139.

- ^ Slovo. 1878. No.2, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Plekhanov, G.V. Iskusstvo i Literatura //Art and Literature. Moscow, 1848. P.624

- ^ Korney Chukovsky. Nekrasov and Pushkin. The Works by Korney Chukovsky. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow. 1966. Vol.4

- ^ Chukovsky, Vol.IV, p.371

- ^ Gippius, Zinaida (1939). "Nekrasov's Enigma (The Arithmetics of Love collection)". Rostok, 2003, Saint Petersburg. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Chukovsky, Vol.V, p.492

- ^ a b Chukovsky, Vol.V, p.472

- ^ Chukovsky, Vol.V, p.484

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International encyclopedia of women composers (Second edition, revised and enlarged ed.). New York. ISBN 0-9617485-2-4. OCLC 16714846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]- Several poems by Nekrasov translated into English

- Works by Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nikolay Nekrasov at the Internet Archive

- Works by Nikolay Nekrasov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- English translations of 3 poems by Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky, 1921

- English translations of 4 short poems

- English translation of "A Friendly Correspondence Between Moscow and Petersburg" in The Hopkins Review

- Some texts by Nikolai Nekrasov in the original Russian

- Nekrasov Library

- 1821 births

- 1878 deaths

- People from Nemyriv

- People from Bratslavsky Uyezd

- Male poets from the Russian Empire

- Russian male poets

- Editors from the Russian Empire

- Literary critics from the Russian Empire

- Novelists from the Russian Empire

- Russian autobiographers

- Satirists from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century poets from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century novelists from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire

- Deaths from colorectal cancer

- Deaths from cancer in the Russian Empire

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery (Saint Petersburg)