Rudolf Hoernlé

Augustus Frederic Rudolf Hoernlé CIE (1841 – 1918), also referred to as Rudolf Hoernle or A. F. Rudolf Hoernle, was a German Indologist and philologist.[1][2] He is famous for his studies on the Bower Manuscript (1891), Weber Manuscript (1893) and other discoveries in northwestern China and Central Asia particularly in collaboration with Aurel Stein. Born in India to a Protestant missionary family from Germany, he completed his education in Switzerland, and studied Sanskrit in the United Kingdom.[2] He returned to India, taught at leading universities there, and in the early 1890s published a series of seminal papers on ancient manuscripts, writing scripts and cultural exchange between India, China and Central Asia.[2][3] His collection after 1895 became a victim of forgery by Islam Akhun and colleagues in Central Asia, a forgery revealed to him in 1899.[4] He retired from the Indian office in 1899 and settled in Oxford, where he continued to work through the 1910s on archaeological discoveries in Central Asia and India. This is now referred to as the "Hoernle collection" at the British Library.[2][3]

Life

[edit]Rudolf Hoernle was born in Sikandra, near Agra, British India on 14 November 1841,[2][3] the son of a German Protestant missionary family. His father Christian Theophilus Hoernle (1804–1882) had translated the gospels into Kurdish and Urdu, and came from a family with a history of missionary activity and social activism in southwest Germany.[2] Hoernle at age 7 was sent to Germany to be with his grandparents for his education.[2][1]

Hoernlé attended school in Switzerland, then completed theological studies in Schönthal and the University of Basel. He attended theological college in London in 1860, studying Sanskrit under Theodor Goldstucker from 1864 to 1865.[2][3]

He was ordained in 1864, and became a member of the Church Missionary Society. He returned to India in 1865 as a missionary posted in Mirat. He requested a transfer from active missionary service, and accepted a teaching position at the Jay Narayan college in Varanasi (Benares Hindu University), coming in contact with Dayanand Saraswati of the Arya Samaj movement. In 1878, he moved to Cathedral Mission College in West Bengal as its Principal (University of Calcutta).[2][3] He joined the Indian Education Service, where the Government engaged his services to inspect coins and archaeological deposits, a role expanded to the study of discoveries related to India in Central Asian archaeological sites.[2][4]

Hoernlé was elected the President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1897.[3] In 1899, at age 58, he retired and settled in Oxford. He continued to publish his studies from Oxford, including his Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India in 1907.[3] He died on 12 November 1918 from influenza.[1][2]

Work

[edit]

Hoernlé spent nearly his entire working life engaged in the study of Indo-Aryan languages. His first paper appears in 1872, on the comparative grammar of Gauri languages. In 1878, he published a book on the comparative grammar of north Indian languages, which established his reputation as an insightful philologist as well as won him the Volney Prize of the Institut de France.[3] During the 1880s, he published numerous notes and articles on numismatics and epigraphy in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and the Indian Antiquary, along with translations of medieval era Hindu and Jain Sanskrit texts.[3]

His first fame to deciphering ancient archaic Indian scripts came with the Bakhshali manuscript, which was a fragmented pieces of a manuscript found in 1881. The fragments remained an undeciphered curiosity for a few years till it was sent to Hoernle. He deciphered it, and showed it to be a portion of a lost ancient Indian arithmetical treatise.[3]

Hoernle is perhaps best known for his decipherment of the Bower Manuscript collected by Hamilton Bower in Kucha (Chinese Turkestan).[4][8] Bower found the birch-bark manuscript in 1890 and it was sent to Hoernle in early 1891. Within months, Hoernle had deciphered and translated it, establishing it to be a medical treatise and the oldest known manuscript from ancient India.[3] His fame led the British India government to seek more manuscripts and archaeological items from Xinjiang (China) and Central Asia, sending him 23 consignments of discoveries before he retired.[2]

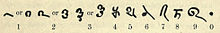

In 1893, Hoernle deciphered the Weber manuscript – one of the oldest preserved Sanskrit texts on paper. He identified the chronological evolution of Brahmi script, early Gupta script and a host of other scripts along with the nature of substrate they were written on (birch-bark, palm-leaf, paper).[6][9]

He was an early scholar of Khotanese and Tocharian languages, which he had sensed as a different Indo-Aryan language in some of the texts that formed the Weber manuscript.[10]

Victim of forgery

[edit]As his breakthrough studies gained fame, various governments including the British government sought and offered handsome rewards for ancient manuscripts. This led to major forgeries, and Hoernlé was deceived by some. Hoernle was concerned about potential for forgery, as some of the fragmentary manuscripts he received appeared to contain Central Asian scripts but made no sense in any language.[4] Hoernle tended to assume good faith and spent time analyzing, making sense of them.[4] In past, his patience with the unknown languages ultimately led to the discovery of Khotanese and Tocharian languages.[2]

The first forged manuscript came from Islam Akhun, purchased by George Macartney and sent to Hoernle in 1895. Thereafter several more Akhun manuscripts followed. According to Peter Hopkirk, Backlund stationed in Central Asia wrote to Hoernle, informing him of his suspicions about Akhun's forgery, and reasons to doubt purchases from Akhun. However, Hoernle found reasons to dismiss Backlund's concerns and continue his analysis of manuscripts sold by Akhun, stating "if these are copies freshly produced, then they are copies of ancient manuscripts" just like reprints of old books.[4]

In a preliminary report in 1897, Hoernle wrote about the new manuscripts he had received from Khotan, the following:

...[they are] written in characters which are either quite unknown to me, or with which I am too imperfectly acquainted to attempt a ready reading in the scanty leisure that my regular official duties allow me ... My hope is that among those of my fellow-labourers who have made the languages of Central Asia their speciality, there may be some who may be able to recognize and identify the characters and language of these curious documents.[11]

Thereafter, he published A Collection of Antiquities from Central Asia: Part 1 on them. The truth about the forged manuscripts by Islam Akhun was confirmed during a site visit to Khotan by the explorer and long term collaborator Sir Aurel Stein and revealed to Hoernle.[12] Stein found many manuscript fragments similar to the Bower and Weber manuscripts in different parts of Central Asia but found nothing remotely similar to those sold by Islam Akhun and ultimately delivered through Macartney to Hoernle since 1895.[2] Stein visited Akhun in person, wasn't able to verify any of the sites Akhun had previously claimed to be the source of his elaborate manuscripts. Akhun first tried to offer alternative explanations, but his workers and he ultimately confessed to the fraud. Stein saw the forgery operations and discovered that Hoernle's good faith was wrong. Akhun and his workers never had any ancient manuscripts they were making copies from.[2][4] Stein reported his findings to Hoernlé, who was deeply dismayed by the forgeries and his error, and upset. He considered acquiring and destroying Part 1 of his report. It had already been widely distributed after being published as a special number of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, and Stein had already disclosed the forgery that formed that collection. Hoernle went ahead and published Part 2, glossing over his personal errors in Part 1, according to Peter Hopkirk. Hoernle did include a note for the benefit of all scholars, stating:

"... Dr Stein has obtained definitive proof that all blockprints and all the manuscripts in unknown characters procured from Khotan since 1895 are modern fabrications of Islam Akhun and a few others working with him".[4]

Hoernlé retired after publishing his 1899 report, his reputation survived this revelation, and his obituaries in 1918 tactfully omitted the incident, according to Kirk.[4]

Hoernle collection, British Library

[edit]In 1902, the Government of India restarted sending consignments to Hoernle, now based in Oxford. He received 12 consignments, which ultimately were transferred to the Indian Office Library in London in 1918, and are now a part of the British Library's Hoernle collections.[2] Hoernle also received all material collected by Aurel Stein during his 1st and 2nd expedition to Central Asia, now split between the British Library and the Delhi Museum. The volume of shipments from India to Hoernle in Oxford increased so much that he could not process them alone. Many Indologists at Oxford helped him sort, catalog and study them.[2] His collaborators between 1902 and 1918 included "F.W. Thomas, L.D. Barnett, H. Lüders, S. Konow, E. Leumann, K. Watanabe, and S. Lévi", states Sims-Williams.[2] During this period, Hoernle and these scholars made significant progress in understanding the scope and scale of Indian literature found in Central Asia, Tibet and South Asia. Hoernle, thus, continued to make his contributions to Indology and published many articles from Oxford during these years. The Hoernle collection of the British Library includes over 4000 Sanskrit, 1298 Tocharian and 200 Khotanese manuscripts.[2][3]

Hoernle collection, Otani University

[edit]In 1920, the Japanese Sanskrit scholar, monk, and later professor at Ōtani University Izumi Hōkei (1884-1947) discovered in a Cambridge bookstore a collection of 431 books from Hoernlé's former possession on Buddhism, medicine, languages, and literature. This collection is now kept in the library of Ōtani University (Kyoto).[13]

Two-wave Indo-Aryan migration

[edit]Hoernle proposed the two-wave theory of the Indo-Aryan migration. According to this theory, Aryans invaded the subcontinent first through Kabul valley, then much later in a second invasion, the Aryans arrived in much larger numbers into a more drier climatic period moving and settling into the Gangetic plains. The second invasion, he proposed, occurred before the Rigveda was composed and before the earliest version of the Sanskrit language took a form. The first invaders spoke Magadhi, the second spoke Sauraseni, according to Hoernle. This theory was adopted by later scholars such as George Abraham Grierson.[14][15]

In addition to his palaeographical and codicological work, Hoernlé published an important series of editions and studies on the history of medicine in South Asia, including a magisterial edition, translation and study of the Bower Manuscript.

World War I

[edit]Hoernle, of German heritage and living his retirement in England, was deeply dismayed by World War I.[3]

Honours

[edit]In February 1902 he received the honorary degree Master of Arts (MA) from the University of Oxford.[16]

He was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) in 1897.

Family

[edit]Hoernlé was the second of nine children. In 1877 Hoernlé married Sophie Fredericke Louise Romig; the philosopher Alfred Hoernlé was their son.[10]

Publications

[edit]- A history of India, Cuttack: Orissa Mission Press 1907

- Studies in the medicine of ancient India, Part I. Osteology, Or The Bones of the Human Body, Oxford, Clarendon Press 1907

- Manuscript remains of Buddhist literature found in Eastern Turkestan; facsimiles with transcripts, translation and notes, Oxford, Clarendon Press 1916

- The Bower Manuscript, Calcutta 1897

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Hoernlé, (Augustus Frederic) Rudolf (1841–1918), Indologist and philologist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2006. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95621. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Sims-Williams, Ursula (2012). H Wang (Series: Sir Aurel Stein, Colleagues and Collections) (ed.). Rudolf Hoernle and Sir Aurel Stein. London: British Library.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m G. A. Grierson (1919). "Augustus Frederic Rudolf Hoernle". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 51. Cambridge University Press: 114–124. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0005259X. JSTOR 25209477.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hopkirk, Peter (1980). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-435-8.

- ^ Rudolf Hoernle, A. F. (1903). "Who was the Inventor of Rag-paper?". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 35 (4). Cambridge University Press: 663–684. doi:10.1017/s0035869x00031075. S2CID 162891467.

- ^ a b Claus Vogel (1979). A History of Indian Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 309 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-02010-7.

- ^ Jesper Trier (1972). Ancient Paper of Nepal: Results of Ethno-technological Field Work on Its Manufacture, Uses and History - with Technical Analyses of Bast, Paper and Manuscripts. Royal Library. pp. 93–94, 130–135. ISBN 978-87-00-49551-7.

- ^ Ray H. Greenblatt. The Vanishing Trove: Reviled Heroes; Revered Thieves. The Chicago Literary Club. 2 October 2000

- ^ "The Weber MSS – Another collection of ancient manuscripts from Central Asia". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1): 1–40. 1893.;

A. F. Rudolf Hoernle (1897). Three further collections of ancient manuscripts from Central Asia (JASB, Vol LXVI, Part 1, Number 4). Asiatic Society of Bengal. - ^ a b Sweet, William. "Hoernlé, (Reinhold Friedrich) Alfred (1880–1943)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/94419. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Hoernle, A. F. R. (1897). "Three further collections of ancient manuscripts from Central Asia". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 66: 250.

- ^ Susan Whitfield (editor), Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries (2002), British Library, pp. 5–8.

- ^ IKAI, Yoshio (2022). A catalogue of the Hoernlé Collection kept in Otani University. Ikai Yoshio. p. 1-70.

- ^ George Erdösy (1995). The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. Walter de Gruyter. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Haigh, John D. "Grierson, George Abraham". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33572. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "University intelligence". The Times. No. 36695. London. 19 February 1902. p. 7.

External links

[edit]- 1841 births

- 1918 deaths

- Deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic

- Linguists from the United Kingdom

- Central Asian studies scholars

- Companions of the Order of the Indian Empire

- Academic staff of the University of Calcutta

- Presidents of The Asiatic Society

- German Indologists

- German expatriates in India

- People from Agra

- Banaras Hindu University people

- University of Calcutta people